Before I start this not-so-long piece that I wrote as quickly as possible: I’d like you to draw attention to another creative endeavor of mine.

I recorded a chill hip-hop / R&B / afro set at my house in BLR recently, to complement a real-time visual of the weather outside. You might want to listen to it while reading this, especially since this is also about music :)

Without further ado, let’s get into it!

Sometime earlier this month, one Saturday night, me, my girlfriend, and my flatmate (and one of my closest buddies) were on a YouTube trip.

We were looking for videos that showed the samples behind popular Bollywood songs. Most of these videos were naturally wowing us; we were in awe of the creativity of our producers who took from international tunes and gave them an Indian veneer to make them popular forever.

One producer in particular took so much from Turkish music specifically that I was lowkey impressed by his plagiarism. In other words, he was commodifying Turkish music for Indian markets. He’s far from the only Indian culprit, but he is the most infamous one. I am, of course, talking about Pritam.

I think it’s hard to not be impressed by him, and I say this begrudgingly. Pritam has topped so many people’s Spotify Wrapped lists that the streaming age just amplified his already-outsized impact. He’s the culmination of what commodified music looks like, and I don’t mean that in a purely bad way. He has an ear for what really works, and will literally go any distance to find those tunes (even Turkey), and his ability to go that distance is backed by a strong team/label.

Anyway, the next Sunday morning after belting some tight ghee podi masala dosa for Sunday breakfast, I was chatting with my girlfriend about Campa Cola.I know, it was an enthralling conversation to have on a Sunday morning. From Pritam to Campa Cola, really?

But I’ll make a connection between them soon. At work, I was writing on the strategy Reliance was pursuing in order to get Indians to consume a cola that, for once, was made in India. My girlfriend’s job involves doing a lot of market research to see what people like their fast-moving consumer goods to have or to say.

Both of us felt like Reliance was attempting to brute-force their way into an industry dominated by two American giants (and some local players that I like) — the same way it did in the telecom industry when it launched Jio some years ago. Few markets feel as saturated as the one for soft drinks, though. Unless your formula is truly different, Coca-Cola will remain the de facto synonym for cola. It’s a proper noun that became a daily-usage verb of its own, which is not a phenomenon too many others can claim to have effected.

But that’s the thing — cola is commodified to an extent that few things could possibly change the market further. What else can Campa Cola do, really? I mean, sure, nationalism sells, so it’s doing that, but it certainly doesn’t sell more than the idea that your product a) shouldn’t suck, and b) should at least be available on the shelves of your nearest kirana store (see the comments section on this video to see what I mean). The brand itself has a lot of nostalgia, but Campa is purely a country for old men — I’m fairly certain Gen Z couldn’t care less for it.

So, Reliance does what it does best — drop its prices so low that everyone is compelled to take notice. Because how else do you commodify a market that’s already commodified? You know how there’s that saying from Jeff Bezos about someone else’s margin being his opportunity? That’s usually true, but Reliance would go so far as to say that unless your bottom-line is painted bloody red, you’ve barely tasted opportunity.

This piece isn’t about cola, obviously. It has more relevance to the Saturday night we looked into Pritam’s work than the morning after. But somehow, somewhere, Campa Cola and Pritam represent the same things. They are both symbols of commodification, embodying the good, the bad, and the ugly of it all.

But Pritam was an edge case of success that people actually appreciate for the creativity involved, despite the “popular music” tag it gets. If you’ve been paying attention — or not, because your lack of it may be precisely why it hasn’t worked — Bollywood music has been sucking big time. None of the tunes really sound memorable anymore. They’re copies of commodified afro house music, and being a copy of a fake sounds like drugged-out people playing musical chairs in hell. A sonic nightmare blunt rotation.

I have no idea why I’m writing this per se. It isn’t even an out-and-out takedown of commodification, but rather why it’s important to remember that music fundamentally resists it. Music isn’t like other commodities that are mass-produced — it’s not cars, it’s not TVs, and it’s certainly not cola. To view music as a vehicle for short-term profits defeats the purpose of not just music but also profit.

It’s the artistic equivalent of “play stupid games, win stupid prizes” and I’m mostly here to say why. Unlike a lot of my pieces, this won’t take long.

Popularity contests

I’d like to start by saying that the commodification of music is mostly inevitable.

However, I don’t say this necessarily with a lot of cynicism. It doesn’t have to be all bad. If you’re AR Rahman putting basslines in your music when no one else did, that will catch a lot of notice. It will get more producers to do the same, because before ARR, it felt unintuitive, and now it looks profitable. And sure, they might not do it as well, but they know that this is the new wave of music. They might as well die trying to copy it badly rather than not at all.

Certain waves of commodification were genuinely quite good. Take, for instance, the dance-pop wave. Artists like Madonna figured out that pop could really benefit from a splash of disco and house music elements. So, she made songs that exemplified those elements, like Vogue, Into The Groove, and countless other hits. Every female popstar who came after her, from Kylie Minogue to Britney Spears, owed tribute to Madonna for starting that wave.

Marketing is a key part of commodification. Popular music needs a story that can be advertised on the biggest screen possible. For Kanye West, it was the idea that hip-hop lacked the feel that would ensure it gets played the same way in huge stadiums as “Bohemian Rhapsody” — which was how Graduation was born. For 50 Cent, while it wasn’t orchestrated, it was getting shot right before the release of Get Rich Or Die Tryin’ (touche). For The Weeknd, it was, well, sex and drugs wrapped in a persona which he probably actually doesn’t share a lot with. And every artist who’s come after each of these guys I’ve mentioned here has tried to emulate their style and success.

And it’s much better when there’s competition involved. Tupac and Biggie, Shreya Ghoshal and Sunidhi Chauhan, Madonna and Cyndi Lauper, Britney Spears (who did a Pepsi ad) and Christina Aguilera (Coke). These rivalries are almost entirely commercial, often the product of myth-building done by fanbases. They’re hardly planned, and even when they are (by labels), it’s mostly just for show.

Now, what you read was commodification through marketing. There is also the technology side of things. Until the advent of music software, you could only use instruments to make music — maybe a beat machine, if you could get one for cheap. The computer made music production accessible to anyone with a laptop. You didn’t need a physical guitar anymore to recreate its twang, you could get FLStudio to do it for you.

I’m not really sympathetic to the arguments against technology in music. There used to be a time when electronic music was called inorganic simply because it didn’t involve real instruments. But this argument always mistook a touch-and-feel sensibility for musical authenticity. You couldn’t possibly argue after listening to Daft Punk’s Discovery that it didn’t rouse you like a rock band would. That it didn’t come from the heart just because the music was made with buttons. The method may be unconventional, but the music was always real.

But more importantly, this argument represented a fear that did not ever fully realize itself — that instruments would cease to be used altogether. That is hardly true. Music is a game of skill whose value lies in not in capability, but creation. Now, the gear you might use to play that game might change — the piano is just one form factor of music. For all you know, music can be made by banging your slippers in rhythm, and anyone can do it. We have never, ever stopped observing the game itself, be it drum solos or slick transitions on a DJ console.

This is also why I don’t get the complaint of there being too many DJs. That every cheeky bugger with a $100 console is calling themselves a DJ. My answer is: let them? DJ technology dropped the cost curve for DJing for so many people, that you could do without buying expensive vinyl sets to start doing some sweet transitions. Like, this YouTube comment doesn’t sit well with me.

Think Different

Which lands me to what you were probably expecting this piece to say. That commodification isn’t really as high and dandy as I make it out to be.

That’s obviously true. Between Spotify getting AI bands to chart on its most popular playlists, to afro house being fully butchered by certain artists (yes, I mean Keinemusik), brute-forcing music for profit has had its fair share of pure rumble-and-tumbles. Commodification makes chasing hits (as opposed to discovering them in a trial-and-error process) the name of the game. And that game can be ugly when it’s played without any consideration of the roots of that music. This neither involves good marketing nor a technological shift.

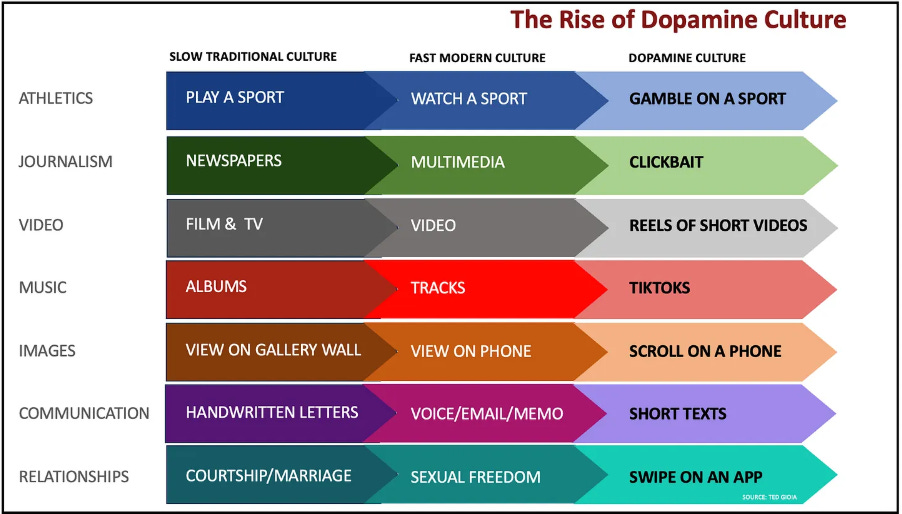

Obviously, while enabling the marketing layer further, social media has amplified this problem I’ve mentioned above to an unfathomable degree. You may have read Ted Gioia’s wonderful (and scary) piece on enshittification and dopamine culture. And you’ve probably seen this chart of his.

But it was never my intention to really elaborate upon these well-known complaints. What I’m really here to say is that some of these cheap tricks to get people to consume music are, from a music business point-of-view, futile business moves in the long run. When you hear enough complaints about music being a certain way, you can almost always guarantee that the status quo won’t last forever. People always use their brains, they aren’t idiots.

Take this reel about DJ gigs being commercialized like music festivals. I’d like you to watch it, because the guy is spot on with how intimate club gigs have turned into commercial festivals, where every moment isn’t optimized for dancing but for shareable Instagram content.

Now, he’s right in almost everything he says. Almost, not because I disagree with him, but because he misses something: that private equity fundamentally misunderstands music as a commodity. The revenue extraction-risk minimization model he talks about has an obvious (and I think short) lifespan. When one risk gets minimized, other risks open up.

Why are DJ gigs being festivalized? It’s to farm content on social media — so it only works as long as social media content pays. What happens when, well, the payouts from content start dipping? What happens when people start getting tired of the music? What happens when in your 6 DJ lineup, 5 have the same 2 songs? That’s when people start asking “where’s the skill in this, anyone can play a popular song and get away with it?” I mean, for ages, people have already been asking what the skill is in being a DJ. There’s no doubt they’ll ask similar questions about club gigs.

The problem with commoditizing something is that sooner or later, you get bored of your commodity. There’s always room for something new and shiny, and that depends on how differentiated the product can get. You got the latest FIFA game? Congratulations for wearing the clown hat, it looks the same as the last one. Nothing feels new about it. The latest iPhone has no new features, Huawei’s and OnePlus’ products look better. As long as there’s scope to make a differentiated product, the status quo is always going to fall short, and that’s worth remembering.

Nowhere is this more potent than in music. Product differentiation is extremely high in music, even if, in the short-term, it helps to just make more of the same. Why music has a lot of product differentiation is because authenticity is a big part of how we consume music. We value artists who tell great, new stories.

After Bob Dylan was found by Columbia Records, the hunt was on for the next Bob Dylan. Bob Dylan (and American folk music broadly) was now the effective commodity. Labels were producing cheap Bob Dylan-esque ripoffs to cash in on the wave. If this sounds familiar, you can replace “Bob Dylan” with “iPhone”.

Except, a) looking at folk music the same way as smartphones is stupid because of how different they are in product type, and b) the wave of American folk music (like many other genres) eventually died out. There was never really going to be another Bob Dylan, he was one of one, a unique medley of the times he lived in and the lives he interacted with. Bob Dylan had become the solution to a problem that didn’t exist before he was discovered. His stardom caused a new cash grab that yielded pretty middling results.

And you could name plenty of genres like that that died naturally. American folk, grunge, Britpop — all products of a certain time. What I really wonder is how many genres went through the same miserable cycle of labels looking for the next Bob Dylan / Nirvana / Coldplay, effectively putting blinders on changing the paradigm of music altogether by searching for new, unique artists.

If you want an easy parallel to understand this, just look at Bollywood. Its problem statement has always been framed as: “how do we replace the stardom of Shah Rukh Khan”? But what it should probably be is: “how do we find good talent?” At the risk of oversimplification (I’m willing to take my chances), the stagnation of that industry can be boiled down to this error — to the point where the current solution to replacing SRK is….get his son on-screen?

Turns out, the music industry is not that different, because how it treats (or mistreats) new blood is a pretty good symptom for how that industry will evolve. Double-click on this next video to see what I mean (not from the start, but from the given timestamp) — just watch 20 seconds.

In fact, much like with music today, private equity once tried to enter film and was likely met with a similar backlash about money spoiling the art. But, interestingly, PE got their hands burnt. The risk-reward ratio in the film industry was too high for them to get into the game again. And much like music, films have massive potential for product differentiation. Look where making all those shitty Marvel movies has landed Disney today — at the risk of being a dying company that simply can’t innovate anymore.

I found this fun comment on Reddit about investing in film, which emphasized that success hinged primarily on loving films. I expect funds to come to a similar realization about club gigs and music festivals — that why people love a certain piece of music or film matters a lot to any business model in the entertainment industry.

How I look at a phenomenon like the festivalization of club gigs is similar to how, at some point in the last 10 years, every product was subject to the subscription model. Digital goods, physical goods, didn’t matter. People thought subscriptions would become the one-size-fits-all dominant business model in the world. That has obviously not turned out to be true anymore.

Authenticity is baked into how we consume music and even produce music — even if it’s hardly mixed and mastered. There has never been a time when we didn’t like our music to have stories. And that has never changed — not just for music, but for every commodity in Ted Gioia’s chart except handwritten letters. We still hugely value real film, real journalism, probably more so because they look really good today in contrast to the stink coming from short-form content.

As long as you’re looking at music from an inauthentic lens, sooner or later, the chicken always comes home to roost for your business metrics.

The New Abnormal

What the brute-force commodification of music misses is how innovation in music happens in the first place.

Let’s go back to that Bob Dylan story. I’ve narrated this story before, but if you haven’t read the piece where I did it — Columbia had no faith in him. They absolutely didn’t think he would be a rockstar or American folk music would be a hit. But music scout John Hammond played hardball with his label and convinced them otherwise. Of course, since then, they knew not to doubt Hammond’s ear (they did once more, though, with Leonard Cohen).

Music is never planned. It’s tinkered upon at the margins, like the early caveman hitting at two stones randomly only to realize that this produces a spark that can light a fire. You have to love it a lot to keep tinkering at that one snare drum for 2 years until it sounds like magic. You’ll know when you’ll have struck gold. You’ll have the kind of face that JAY-Z had in Timbaland’s studio when he first heard the beat that would eventually become “Dirt On Your Shoulder”.

Second is a trend that music industry professionals have been keenly watching (see the tweet screenshot below). The product differentiation so inherent to music has been translating to a more natural outcome — that of niche fandoms. The end state that many project for this is that the future of music won’t be marked by a few superstars at the top (as has been the case for long), but many mid-tier stars who have sizeable (but not Taylor Swift-level) fanbases. The end state may not be as strong, but it’s certainly headed there, and it’s partly because of the type of commodity music is.

If you think about it, it’s not that far off from the restaurant space. You have your big chains and all that, but you know the gourmet shit only comes from that one restaurant that few frequent: but those who do, they swear by it.

This decentralization has larger implications: what does it mean for mass production in music (and artistic industries overall)? Certain genres/industries did follow a factory model (see: K-Pop), but it soon lands into a diminishing returns problem. Even if the factory model isn’t borderline exploitative, and is just your average team of songwriters, engineers and marketers surrounded by a popstar, it still doesn’t solve the problem of discovery. Your label-assembled rockstar team is now an echo chamber with little outside connection to the independent / underground scene.

And this is going to be even more painful in the AI age, where the pop song faces further devaluation. Platforms like Suno will swing the pendulum in the opposite direction — where being authentic matters more than ever. For the record, we’re seeing this exact pendulum swing in the writing field.

With music, one is hopeful about decentralization driven by a confluence of a) granular marketing, b) better technology, c) a more demanding, less voluminous fanbase that wants to see you live. This, in turn, might render a mass production mindset more useless than ever. This isn’t to say labels will stop existing, but it is to say that how they operate now might need re-thinking.

I’m mostly sending in this draft unedited (I probably should have checked it with a friend in the music industry), so I had no real agenda to push here that I haven’t pushed already.

If you’ve been a reader of Hot Chips, you probably already know that music is something I feel strongly about. And it matters to me that good music gets out there. Big star, small indie player, doesn’t matter.

Over time, this involves asking a lot of questions. Is popular music necessarily always good? What does it mean to be “making music for yourself”, considering that we always feel the need to have an audience for our art? What does it mean to consume art?

I don’t have clear answers to any of these questions. But what I do know is that no matter what, one thing is constant: more often than not, good music wins. Conversely, complacency in music never helps. It’s the beginning of your descent as a musician who builds and curates new tastes.

There’s always going to be good music. And, like always, it’ll come from places you’ll never expect, in ways you’d never imagined, with emotions you’re yet to discover.