Fight Night

How Hasbulla and Abdu Rozik are poised to dominate with their brands.

Hi folks!

It’s nearly one year to Hot Chips, and I haven’t had any time to think about how one year of this newsletter has flown by. Life’s become pretty hectic, which might explain this delay. But I’m not complaining.

All I do know is I’m glad where it is going, what it’s been through, and I massively enjoy writing this newsletter. I think I can do this for a long enough time without feeling bored, or worrying about the motivation to write something big day in and day out. And I’m glad that to-date, 350 (!!!) folks have stuck around for this journey :))

That being said: this might have been the toughest piece I’ve done. I’ve been stuck at various points, because I have known the story in my head for more than a month-and-a-half. It had a beginning and an end, but a sketchy middle act. And I had a tough time deciding the song. I wanted this to be as thorough as possible, because I felt like this story could be deeper than what average internet-savvy person might give it credit.

But a few things, and people, clicked. I was able to get some insane insights about the creator economy in general, not just the story I wanted to write. I wish I could use all of them here!

I also needed a track that felt both genuine and ironic in its usage. I know, I know, “Why Drake??” But here’s the thing: he’s the (ew) superstar that embodies traits of both the main characters in this story. So there’s one track for each of these guys, tracks that best resemble them. The 2nd song will come up somewhere in between. They’re also some of Drake’s best, which is great, considering how trash he has been the last 4 years.

I’ll stop.

But I suggest you get a speaker, a can of Coke, and (ahem) a pitzah or borgir to read this :)

The last year or so saw the rise of short king spring.

Conventional societal knowledge states that it’s hard out on the streets of love for a man below 6 feet. Which is why a lot of guys love rounding off their heights to the nearest acceptable benchmark. 5’10” and 5’11” become 6 feet. And on meeting, it certainly feels underwhelming, but you can’t quite place why without a physical measurement scale. Hell, I’m a little short, but I wouldn’t go as far as to do that. If only I had been a basketball fan in my early adolescence instead of now.

But now? It’s hip to be short. What began as a meme song in 2019 from The Lonely Island-ripoff Tiny Meat Gang has materialized into something much bigger:

“Standing 5'8", voice 6'5""

Tom Holland is short, and he’s with Zendaya. TikTok is rife with the hashtag #shortking. Anthony Fauci is 5’7”, and he tried to save an entire country. The short-form video giant was rife with creators who couldn’t see over the dinner table. And the TikToks are about, well, interesting things: how to pose for a short king when you’re a tall queen, how to handle height differences in a relationship, and flexes of how that when God made short kings, they forgot a few inches.

But I suppose no one embodies that last line more than two guys who originally became big on TikTok, measuring a bit above 3 feet, who had the internet in a chokehold by going toe-to-toe against each other.

If He Dies, He Dies

As a region, Russia has its fair share of citizens suffering from growth hormone deficiency (GHD), so much so that hormone therapy for the children who suffer from it is funded by the state. As of 2016, for every 100,000 children in Russia, 1,438 suffer from GHD. Prevalence of GHD also depends on sub-regions in Russia — in some places, it’s really high. GHD doesn’t just affect height, but the three-dimensional growth that a normal homo sapiens goes through, as well as the bone mass.

But not that Hasbulla Magomedov cares. Hasbulla was born in 2003 in a Russian village called Aksha, before moving to Makhachkala. He suffers from a form of dwarfism which has limited his body and voice development. But his position is that his likeness with the most famous (and arguably most talented) GHD victim of all — Lionel Messi — exists beyond just sharing the condition.

He’s 3’3”, and harbors dreams of making it to the UFC. If he couldn’t be as big and laterally quick as his idol — Khabib Nurmagomedov — he was going to imitate him in style and spirit. So he started making videos of himself shadow boxing, imitating UFC fighters, punching his crew and getting away with it slyly.

Since discovering that he has the advantage of looking too innocent for a 19-year old (now 20), he created content around pulling pranks on his friends and crew. And, of course, doing random things on the street. Like bossing the dust around on an ATV, playing with a monkey, and wielding a gun like a gangster. One look at his Instagram might make one concerned as to how much he loves guns. Russian gun laws are wild. On the other hand, his social game also involves functioning as a cat stan account. One of his most popular clips is from last year, of him cutely mispronouncing “pizza”. The original clip got 8.4M views in a month, and got memed to oblivion.

Before you knew it, he was clicking pictures with Khabib, who has pretty much taken Hasbulla under his wing. His favorite past-time is throwing jabs at pro MMA fighters. Khabib, Daniel Cormier, Alexander Volkanovski, everyone has been a a victim.

But all things aside, Hasbulla created a unique image of himself in front of the world. One that is often described by many as “cute but dangerous”, “adorable but intimidating”, “spirited but ready to throw a punch”, and “a player of the highest order”. There’s a Twitter page (@HasbullaHive) dedicated entirely to posting photos of Hasbulla with the corniest of captions about how he’s a ladies’ man. “He’s about to steal yo girl”. Note that HasbullaHive is not run by Hasbulla’s team. It’s a fan account with more than 660K followers. TikTok is full of Hasbulla fan pages that have followers even in the hundreds of thousands. His own is at a 1.3M, while his Instagram crossed the 3M mark only a few weeks ago.

Fan pages, not the actual one.

Before April 2022, not much was known about who he is as a person, until he did his first public interview with Barstool Sports. And, well, he pulled no punches. He annoyed the heck out of the interviewer (and punched him), called him unintelligent, talked about his cat who he wanted to bring to Dubai. Hasbulla has dreams, which may or may not involve holding a pistol on either hand. But he originally wanted to be a trader or a truck driver, only to eventually get into car business.

He claims to have learnt boxing himself. You know what they say about violence: when your guns fail, only your hands can save you. He wants to be the Minister of Internal Affairs for his district, Dagestan, so that he can make his haters parade around the city with him. And remove all speeding limits.

But above all, he will beat up Abdu Rozik till he bleeds to death.

Tajikistan’s Very Own

A piece of the ancient relic that was the Soviet Union, Tajikistan has its fair share of health deficiencies among its citizens, especially women and children aged between 6 months and 5 years. Children were especially susceptible to growth stunts due to chronic malnutrition in their early years — in 2017, a national health survey concluded that 18% of under-5 children suffered from stunting. This is a more critical issue in Tajikistan’s rural areas.

Abdu Rozik was born a year after Hasbulla, in the Panjakent district — the kind of rural area where you would expect to have see such health hazards. He will turn 19 this year. It may not be too far to assume that the two of them meeting could probably be destiny. Abdu had a humble beginning. He too suffers from dwarfism, and had a phase of rickets as a child. He was grossly underweight, much like a fair chunk of Tajik children. His parents, who are both gardeners, weren’t rich enough to afford treatment for him at the time.

However, Abdu had one trait that few people do: an angelic voice. He used to sing in bazaars to earn money, and he tried his hand at shooting videos to see if popularity embraces him. And in that effort, he was discovered by a Tajik rapper named Baron, who took him under his reins to the capital city of Dushanbe, under the label he was part of — Avlod Media. Baron provided financial assistance to him and eventually brought him to Dubai.

Abdu was born to be don the hat of a singer with a forlorn love. And his first tryst with internet fame was a track named “Ohi Dili Zor”, which was published under Avlod. While there’s not been an attempt to translate the lyrics of the song, one look at his emotiveness should be enough to give away the possible theme of the song. Short, adorable king who can sing? Hallelujah. 10M+ people also think the same.

But Abdu’s global appeal came when a clip of him cutely mispronouncing the word “burger” surfaced. He got called the borgir kid. The memes were relentless. He had achieved the status of viral sensation, with 3.7M followers on Instagram to-date.

Abdu’s Instagram immediately pops out — sometimes he’s doing the most adorable things, like standing headfirst on a snowy ground (and tumbling), going to fancy restaurants, doing funny impressions, dancing, singing, and meeting every celebrity he can. For the longest time, his dream was to meet Cristiano Ronaldo — which he also accomplished this year. He’s met everyone — Ronaldinho, Paul Pogba, AR Rahman, Munawar Farqui, Salman Khan, Sadiq Khan. He’s endearing, photogenic, seemingly very approachable, and full of life. In 2021, he became the youngest person from Tajikistan to receive the UAE golden visa — which gives him 10-year residency.

While both Abdu and Hasbulla seem to have had similar come-ups to fame, their external brands, and the way they both present as captivating, could not be more different. Besides boxing, the only other thing common to both of them is that they’re both fairly religious. Hasbulla gives off the vibe that he doesn’t have two shits to give about fame or celebrities. He’s naughty, cunning, sometimes a bit sinister. Most of his pictures contain a grumpy face of him. He embodies the “I’mma get rich and get my homies rich, by hook or by crook” mentality, and that’s all there is to the game for him. He doesn’t care who’s in front of him, or what setting he’s in — they’re all getting a punch when they least expect it. He couldn’t care too much about being a superstar, or being likable. He’s just himself.

Which is not to say Abdu isn’t himself, but it’s almost as if he was always meant to be a blockbusting entertainer — who are, by nature, the subject of a lot of love and adulation. He understands how to capture audiences, how to generate mass appeal, and how to churn hits. He wants to dress and look fancy, live fancy, and have some jolly good fun and laughter while he’s at it, while gripping the world in a chokehold with the supposed innocence of his heart. And unlike Hasbulla, he has no qualms chilling (and making cute reels) with lovely women. He might be more emblematic of short king spring than his slightly-older rival.

But in May 2021, both personalities came to a clash that clasped the internet in a vice. It was the fight to end all fights. Step aside, superheroes and sportspersons, here’s the showdown of the century. It’s “pitzah” vs “borgir”:

Hypebeast Mode

It is entirely possible that both of them are just playing characters. But it doesn’t matter: Hasbulla and Abdu Rozik are aces at building hype around them. So it’d only make sense for them to find ways to monetize their popularity.

The catch is that there’s virtually very little on the internet regarding how both of them are going about brand-building. An attempt to take a stab at it took me to a few interesting places, doing some piecing from their socials, and a lot more enlightenment regarding the journey of a content creator.

I spoke with Avantika Gupta and Rayees Shaikh, two folks from the influencer marketing and social media division from the music label Big Bang Music. A chat with them led to listing down factors that we thought evoked certain kinds of feelings from each account. An analogy that helped frame this was Shah Rukh Khan and Salman Khan: both popular among masses, but known for very different things tonally.

Body language — Hasbulla is almost always stiff. His face is often grumpy, and it feels like he’d rebuff you if you approached him for a selfie. Even if he smiles, it feels like he has something up his sleeve that he wants to surprise you with. Abdu Rozik, however, is extremely expressive: he loves using his hands, and his facial expressions have the range of a Marriott breakfast buffet. His smile feels warm, and he seems very emotive. He’s playful, but not in a sly manner. You can ask him for a selfie, and he would probably agree.

Dressing sense: Hasbulla is the influencer version of rap Drake. Never mind that I was listening to 21 while writing this: Hasbulla has tons of photos where he is actually strapped. And except for when he has to tend to prayers, he’s wearing “I don’t give a fuck” clothes. He is the start of 6 God.

But Abdu Rozik has a suite of suits. He has something for every occasion. He wants attention. He’s pop Drake, he makes songs like Nice For What.

Company: A quick look at who either of them hangs out with gives you distinct impressions. You could replace Mickey and Rocky with Khabib and Hasbulla chasing chickens and it would still be a great movie. You won’t see Hasbulla with any women, ever, even though he gives you the idea that he has that ladies’ man touch. But Abdu is a meet-and-greeter of the highest order. He thrives as an extrovert. Men, women, non-binary people, they all love him.

Andre Agassi might not agree, but image is everything. But a character? You believe in a character, even if its smoke and mirrors. Hasbulla and Abdu Rozik are the main characters in a world where short-form content is commanding authority and attention. PR is king in world-building around a character, and it can be ever so deliberate. As a character, BeerBiceps is someone who the average listener would associate traits like humility, learning, positivity, health, and now entrepreneurship. You could play a drinking game everytime he says he’s humble. But it’s sheer lengths to which his team goes to maintain that character. There is never a content piece that’s not manicured by him. His angel investments in startups (which are fairly recent) make quite some noise — most notably, his cheque for consumer tech company Nothing. If cricketers and Bollywood stars can hire PR, why can’t influencers?

Neither Hasbulla nor Abdu Rozik has had to deal with particularly bad PR yet, but the brands of both these people look so deliberately controversy-free. It’s just two people from humble backgrounds and a couple of physical shortfalls living their dreams, devoid of real-world politics or social issues.

Chasing Bags

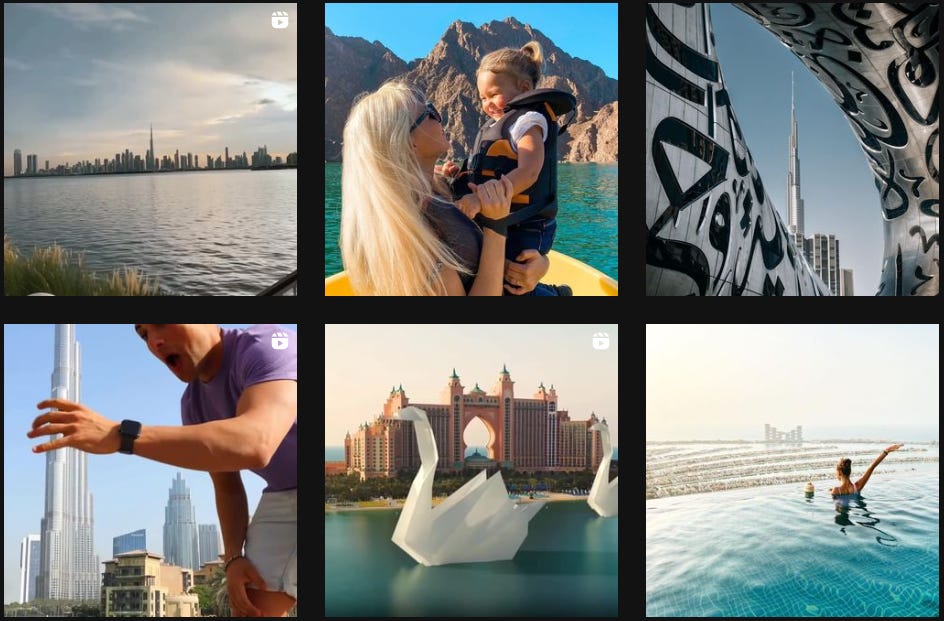

And the dreams are tall. Both of them frequent/live in Dubai, and flex to the point where you ask yourself whether there are any dreams worth more than money. How much the net worth of either influencer is, is yet to be known. With the diverse revenue streams that an influencer may have, your guess is as good as mine.

Both of them surely make money from running ads before, during, and after content on TikTok, Instagram, and in the case of Abdu Rozik — YouTube.

Ideally as influencers, brand deals should come fairly naturally to both, given their following is in the order of millions. But here’s the kicker: Hasbulla, at the very least, is rarely shown doing a single brand deal on his Instagram. The man is pure gangster. There’s no question he must have brands chasing after him every other day. But he’s clearly very selective about being a sellout.

Abdu Rozik, on the other hand, goes to new restaurants every other day, or so say his stories — often to eat burgers. He has no qualms about calling a restaurant that will obviously pay him well for his endorsement the best dessert shop in a given country. Which might raise the question: “Why hasn’t a McDonald’s or a Burger King approached him yet for a borgir deal? What’s the hold up?”

Going by this digital marketing website tracking the world’s most famous Instagram accounts, Hasbulla went from 810K+ followers in November 2021, to ~2.7M in July this year, with a 9% engagement rate — at any given time, at least 230K engage with his posts. He might charge an average of $5K for an image post, and $10K for a video post. The same stats for Abdu Rozik are not public, but considering he’s a contemporary, the costs for him should be fairly similar — maybe a little more, seeing as how he has the ears of some of the biggest celebrities in the world.

However, both Hasbulla and Abdu Rozik would have a more secret source of income: private events. David Royce, a podcaster (link here) and industry operator who operates out of Dubai, tells me that the average amount highly successful influencer charges for a private event is $100,000. And it checks out: Dubai has more than enough propensity to pay to have an influencer entertain them in the dining room.

I had a chat with the official Instagram account of IFCM — the agency that now manages Abdu. They were vague regarding his brand deals, and explicitly refused to reveal any financials. However, the nature of the relationship between Abdu and IFCM was made a little clearer — IFCM doesn’t look at itself as an agency. In its own words: it has no clients, but rather it tries to fund those who have talent but no means to reach. Basically, this implies some sort of financial and networking assistance, beyond its general services I’ve mentioned above. However, what is unclear is if this sponsorship also has an underlying contract with certain conditions as to revenue-sharing, disclosure of deals, and so on. IFCM finds a mention in many of Abdu’s stories and reels, and he repeatedly thanks the agency for his fortune in his posts.

Hasbulla has readily taken up merchandising. An official Hasbulla tee would range in the $40-60 range. It is unclear whether there is actual inventory for his apparel or if there’s some sort of dropshipping involved, but it exists, and it has worldwide shipping. He also has a dedicated subreddit (r/hasbulla), which loves keeping track of every single thing he does — like a shoe line with his name on it that cost $25K. Abdu, however, hasn’t taken merchandising super seriously, yet.

Both of them have also been quick at embracing some newer, more advanced forms of minting money. Earlier this year, both influencers announced their own NFT projects. Hasbulla’s NFT airdrop is an attempt to create an enviable community around him that gets exclusive access to him — both in-person and online. The project is in its 2nd phase (out of 5), and currently, only 2000 of these NFTs have been minted. The end goal is to launch a crypto token in his name, and launch a metaverse game where the NFT holders can play to earn Hasbi tokens. Many NFTs are designed in a way where Hasbulla’s likeness is transposed to that of famous celebrities, characters, and avatars. Holder benefits also vary depending on how many NFTs one owns. It grants one discounts, invites, free flights, and deals with partners — like Khabib, Shaquille O’Neal, Logan Paul, Barstool Sports, and LAD Bible (of all websites).

Abdu Rozik’s project also seems to be similar. His socials mention an “abduverse” — hinting at a play-to-earn metaverse game as well, much like Hasbulla. The larger community roadmap, however, does not seem as well-outlined yet as that of Hasbulla. The first phase will have 5,555 hand-drawn NFTs minted of Abdu Rozik in his different outfits and avatars.

These NFT projects are coming in at a time when creator interest in the web3 world has reached a high. Creators are investing their time in building a strong, high-paying community that can earn from owning a stake in that creator’s journey. Gary Vaynerchuk’s VeeFriends project is a solid example of a successful creator-led NFT project. Of course, the success of a project like this would depend on a) the creator’s social currency, b) the community and how active it is, and c) the NFT’s utility. The creator interest in web3 is also part of a wave of influencers (at least the very sizeable ones) trying to find new ways to monetize their brand. New product lines, equity deals, affiliate programs, NFTs.

Come, See, Conquer

This diversification of bag-chasing probably doesn’t make it too much of a surprise that Dubai has become the preferred choice of place of operations for both of them. Hasbulla has mentioned it numerous times as a city he loves. — here is him chilling with a Dubai-based influencer while facetiming Logan Paul. Abdu practically lives there. Why does the city have that kind of pull, besides the obvious lifestyle improvement it has to offer? Is it an influencer haven of some kind?

One starting point to answer that question might be the Nas Summit which was held this year there. Influencers from all over the world, including a significant number from India, headed over there. It had some venture capital backing — including from GSV and Lightspeed. Companies like Snap, LinkedIn, and for some reason, Barbados Tourism attended the 3-day fest. Clearly the summit was great exposure to many.

But the UAE itself wants more people to adopt the country as home — which is why it has some of the most convenient visa policies in Asia: both for tourists and potential businesses. David mentions that you can legally register a business within 3 days of getting a license. The UAE government believes that influencers have the power to promote Dubai as a possible expatriate destination. So it has people like Abdu Rozik promoting some of its biggest attractions, like the annual Dubai Expo. I spoke to Pranav Panaplia — the founder of an agency called Opraahfx, who refers to the popularity of the #VisitDubai campaign. You can tell what influencer posts are sponsored by peeping that hashtag.

The city became an unofficial influencer capital last year itself — at the height of the second CoVID wave. Hotel chains like Radisson are chipping in, featuring travel bloggers on their ads. Some creators have decided to permanently move to Dubai as well — like MoVlogs and SuperCarBlondie. Indian creators feel the Arab heat too — like Dubai-based Ritu Pamnani, who has cracked a Cosmopolitan cover, among a number of deals in fashion. Influencers on Dubai billboards aren’t uncommon either, as David tells me.

The world has adopted influencers into the mainstream. They’re not just online personalities anymore, but rather people who you might end up seeing on large billboards and TV advertisements. Some people get deals from BBC. Some get deals from Spotify. Some appear on TV commercials — like Awez Darbar and Nagma Mirajkar on McDonald’s. Some like Prajakta Koli get Netflix shows. Big brand deals are one signal of becoming more colloquial, and why not? Brands feel that influencers are more efficient conversion-wise, while charging less than what a conventional celebrity might, and ensuring better Gen-Z connect. This also explains why TVC spends on social media influencers have increased significantly as compared to conventional celebrities.

Some of the bigger ones pull a pivot so big that you forget they ever advocated for something problematic. Pranav gives me the example of Logan Paul — he went from being known for filming a suicide victim in Japan to now being on the same stage as Arnold Schwarzenegger, the same IG live as Drake, and the same frame as the guests he interviews on his podcast — Logic, Mike Tyson, Kevin O’Leary, Triple H, to name a few. It’s also the diversity of what he’s doing that has made his brand strategy so successful. “No publicity is bad publicity” — it would have been pretty easy for Paul to fall out had he continued being edgy after that controversial video.

This sort of mainstream attention is also aided not only by the ability to be forward-thinking, but also enter new markets; sometimes switch to new ones. In the case of the latter, Logan Paul is a great example — his claims to fame have shifted across the years; from hilarious and edgy Vines, to matters more serious. So is Tanmay Bhat — who changed careers altogether in the quest for a successful rebrand where his current audience doesn’t resemble — in size or composition — what it was as a comedian. He’s now much better known for being an advocate of entrepreneurship, personal finance, and deep conversations with accomplished people.

But when it comes to new market entry — if an influencer needs to expand their market to a location other than their home location, the easiest way to go about that market entry is to collaborate with the local influencer of the target location. One of Dubai’s most popular influencers is a man named Anas Bukhash — described to me as the BeerBiceps of the Middle East. He runs a YouTube channel called ABTalks, where he releases podcast episodes with celebrities — Max Verstappen, Masaba Gupta, Atif Aslam, Nora Fatehi. And interestingly, he has one episode with a very popular Indian dude who buys jungle land for a living. You might better know him as Sadhguru — who has been all over Instagram this year for his Save Soil Foundation.

Remember when he had a daily column in The New Indian Express? Me neither. Now he’s seen carrying Abdu Rozik in his arms.

Abdu is on track to being a superstar. He bagged the role of a gangster, in Salman Khan’s next Eid flick — very obviously boringly-named Bhaijaan. He’s driven his India market entry straight into 5th gear in the most explosive way possible — entering Bollywood. All the while, multiple Indian influencers, actors, comedians and bosses of music labels, create Instagram stories and reels with him. Of course, much of this may not have been possible without the network of Abdu’s “sponsor”, IFCM. Bollywood will ensure he’s in everyone’s minds rent-free after he’s on the big screen.

The production team behind the Ranbir Kapoor-starrer Shamshera invited an entire summit of creators for promotions — proving that even an effective marketing campaign can’t save a bad movie. But more importantly, Bollywood stars are realizing the power of building an online presence. Some of the biggest Hollywood actors and sports superstars figured out early on that YouTube is extremely effective, and much easier than shooting film. Will Smith, The Rock, and now Varun Dhawan and Kartik Aaryan — who actually has more 200K more subscribers than Dhawan. Or Indian TV actress (and Kota Factory star) Ahsaas Channa, who got 3.4M followers on Instagram through dance reels, vlogs, and fashion and makeup tutorials. Are actors increasingly pivoting to being social media influencers? The answer is a yes, and the line between the two gets blurrier with time — more actors taking to social media influencing, more influencers trying to enter acting.

And this kind of mainstream attention was not really a goal for influencers in the beginning. The start was all about blitzscaling their content, and the process of making content. Siddhansh Agarwal, an insider in the creator economy (and whose Instagram account is quite the popper), says that going mainstream was only a by-product that eventually turned into a blueprint. However, that doesn’t underlie its importance to those who chase it. Influencing is not a traditional career path, and requires more than a little acceptance from society. Then what better way to prove that you’ve made it than on a front-page ad in a national daily? Or film?

But the mainstream also brings with it a fear of saturation. “The moment an influencer appears on a TV ad, they stop becoming an influencer”, says Avantika. The concern also comes with the perceived yield from sporting an influencer on huge advertisements. Diminishing engagement and conversion rates from macro-influencers, Avantika states, might force brands to re-orient their strategies a little. But if you’re on one of those huge screens, you might as well be a celebrity.

Hasbulla, though? Hardly any celebrities in sight when it comes to his mentions. He’s not concerned about popularity contests or new markets or any of this. He just wants what we call the bag. When asked about Abdu Rozik meeting Cristiano Ronaldo, Hasbulla mocked the Portuguese footballer’s style of play, and called himself a bigger celebrity. His most talked-about public sighting in recent memory is a trip to Australia, which was organized by a management company called The Hour Group. Their past arrangements include Kobe Bryant, Anderson Silva, Khabib himself, Jhene Aiko and Tyga. This year, they’ve called Hasbulla and Shaquille O’Neal, and I would have not commented on the certainty of their paths crossing. Until this happened while I was writing this piece. Even Kobe never got away with punching Shaq.

Maybe Hasbulla doesn’t just want to settle for something small. Literally and figuratively, he wants big men.

LET’S GET READY TO RUMBLEEEEEEEE

Much of Hasbulla and Abdu’s come-up boils down to, and also stems from, the clip that made both of them extremely famous. The prospect of an MMA fight between them has kept the followers of both on their toes.

But, um...what’s with all these influencers and MMA fights? And why does either person want a UFC fight with the other so bad? We’ll need to do a little rewind for this, because key to getting to the answer to the first question is understanding the hype and economics of a widely advertised mixed martial arts bout. Bear with me.

The UFC is the most well-known brand when it comes to MMA fighting. Right now, we often associate high-profile UFC fights with exotic locations, the world’s biggest sportspersons and celebrities showing up, and a ton of pre-fight press conferences. But there was a time when MMA fights were not accompanied by a lot of fanfare.

The first UFC event ever took place in 1993, and it was pitched as an 8-man single elimination tournament, with no weight categories or time limits, much unlike today. This took place in Denver — a city with no regulations around boxing. It drew more than 86000 paid viewers, pretty impressive for a first outing. But it struggled in the 90s, because of how it was perceived to be violent, and the fact that it started to face some political heat. One future presidential candidate called it “human cockfighting”. In fact, it was doing so bad, the parent entity, Semaphore Entertainment had to sell the “UFC.com” domain to some random company called “User Friendly Computers”. It had to strip itself of everything except the UFC brand name, and the infamous octagon where the fighters spar. More like octa-gone.

Enter Dana White — the current president of the UFC. White has seen some shit — including an alcoholic dad, a divorce, dropping out of college, and a supposed encounter with infamous mobster Whitey Bulger. He used to work as a boxercise coach. He started training under a Jiu Jitsu expert named John Lewis, who was also competing in the UFC. This led him to being connected to, and eventually becoming the manager of two fighters — Tito Ortiz and Chuck Liddell.

While managing them, White met Bob Meyerowitz — the owner of Semaphore Entertainment. Bob told him that he was looking to sell UFC, at which point White linked him with a childhood friend of his named Lorenzo Fertitta — who made significant money running casinos, and was also the once-chairman of the Nevada State Athletic Commission. Lorenzo and his brother Frank purchased UFC under a parent entity called Zuffa for $2M in 2001. White was instated as president.

By 2015, UFC became a cash machine, making $600M in gross revenue. White explored and unearthed new fighters from regions outside America — arguably the biggest one of the 2010s was an Irish bloke named Conor McGregor. In 2016, when Zuffa got sold to Endeavor Group, UFC was valued at $4B — the largest ever valuation of any sports franchise at the time. In that new valuation, it saw 23 celebrities who put $250K each as angel money. White ensured that each major fight was backed by huge sponsors. Everyone from Kevin Durant to Donald Trump shows up at a major fight. Today, the annual revenue of UFC is around $1B. UFC is possibly singlehandedly responsible for the popularity of competitive MMA as a sport. And Dana White is the main driving force behind this outcome.

Why influencers started using competitive MMA as a tool to prove who’s better, no one can say for sure. What I can say is that one of the content creators who helped popularized MMA actually started off as a color commentator for the sport. He’s best known for his extreme reactions at knockouts, and taking in a drug called MMT. He also signed the biggest Spotify podcast deal ever in the Joe Rogan Experience.

But otherwise, the thinking around doing one is simple: there’s a lot of money to be made (which we will come to), and status levels to be climbed, in a standard fight.

Roll back to 2018. A British YouTuber named KSI challenged Jake and Logan Paul to a bout for the YouTube Boxing Championship Belt — an unofficial trophy that was minted for KSI after he won a fight against another YouTuber named Joe Weller. It was just bragging rights, but the fight was very real. The press conferences were brutal — families and girlfriends were proxy victims in a war of words, much like tours of real MMA pros. Avid fans of the YouTubers brawled with each other pre-fight. The result of the fight doesn’t really matter (draw), but this was the start of a trend where extremely popular content creators went gladiator-style against each other to prove who had bigger balls. YouTube numbers? Pfft. Old school.

Maybe a regulated fight is an acceptable way to have grown men use their fists, because KSI was serious about becoming a professional fighter. But MMA, like any other sport, isn’t easy. It didn’t stop influencers from going beyond their ambit — Logan Paul called on boxing legend Floyd Mayweather for a match. I need not tell you how that ended. More recently, the royal prince of wolfpack incels, Andrew Tate staked a Bugatti worth £4.1M for a fight with Logan Paul. And in case it isn’t clear already why — Logan Paul himself admitted that he would love to monetize the sudden rise in Tate’s popularity over the last few months.

The fight with KSI also worked. A quick look at the highlights of Google Trends in 2018 — the year of the fight — will be sufficient to say that, well, it was more than a huge success, at least for Logan Paul. He was on everyone’s mind.

The Hasbulla-Abdu Rozik fight, then, should come as very little surprise. But they have a lot more reason than just bragging rights. Hasbulla hails from the same region that Khabib calls home. His come-up to ~3M followers on Instagram partly involved posting funny clips emulating the legendary fighter. He is extremely passionate, possibly to a fault, about MMA as a sport. He is unironically putting in some serious time in the weight room. He makes regular appearances at actual UFC fights, and Khabib’s club’s events. The man in the clip where Hasbulla and Abdu traded punches for the first time ever was Hasbulla’s ex-manager, MMA fighter Asxab Tamaev. This fight has been more than a year in the making. Here’s an entire video of Hasbulla punching MMA champions:

It’s pretty vague as to where Abdu’s interest for MMA comes from. It is worth noting two things though — a) he’s listed as a brand ambassador for the World Boxing Championship, and b) IFCM — the agency that represents Abdu Rozik — stands for International Fighting Championship Management. Their service offerings are very much in line with what you’d expect from a talent management setup: paid celebrity meet-and-greets, original merchandise, event management (concerts, private events), et al. But true to name, this agency does one other thing that most others might not: sports events. The website only lists two other clients:

Yousef Al-Matrooshi — a 19 year-old international-level swimmer, who also competed in the Olympics for the first time in Tokyo. He was the flagbearer for the UAE contingent, and his ambition is to become the first Emirati to compete in 3 consecutive Olympics.

It doesn’t make a lot sense for a swimmer to be represented by a talent management agency this early. For starters, he has 5200+ followers on Instagram — nothing in comparison to Abdu’s monster 3.7M.

But it may be important to set a little context. The UAE only sent 5 competitors from 4 disciplines to Tokyo 2020. 2 of those are not originally Emirati. Since 1984, which is their first appearance in the Olympics, the UAE has won only 2 medals — a gold and a bronze. Backing a 19-year old swimmer then seems like an early bet.

Jad Hadid — a Lebanese model and actor. He has 370K+ followers on Instagram, has some TV appearances under his belt, and major collaborations: Quaker Oats, Reebok, Toblerone, Lipton. He also has a really cute Apple Music playlist dedicated to his daughter, who is plastered on what is otherwise the IG wall of a hot Arab man with a lot of motivational speeches in him.

Then what’s the hold up? One answer (out of two alternatives) might be, as you might have guessed it already, the moolah.

Fighters in UFC get paid depending on how popular they are. For any given bout, both fighters involved negotiate their contracts separately. This is a list of payouts for all fights under UFC 229:

There are three tiers of fighters in UFC. Someone like Conor or Khabib, who would belong to the highest tier, should get paid more than $500,000, ideally closer to the million mark. These fighters will pull in sponsors and attention for the pay-per-view event that will eventually get broadcasted. For example, UFC 229 has Conor vs Khabib as the headliner, or the main card. But paying a fairly hefty amount, like $80, doesn’t make sense for just one fight, even if it’s between the best in the world, and even if it includes some “yo wife” insults between grown men. The cheapest ticket for UFC 229 was $205. So other fights are lined up as part of the 229 card between mid-tier fighters.

One observation in the image is that all fighters except the top-tier ones get a win bonus, which is usually double the fight money. Top fighters aren’t generally privy to a win bonus (not that they need it). But these fighters have the ability to call shots on something more lucrative: a cut of the pay-per-view revenues. This also creates an incentive for the fighters themselves to promote the main card. If this means having some fun antics at press conference tours — some of which span countries — so be it. This also means that they can get some personal sponsors. Conor might have made $3M from the fight, but he made $50M overall from UFC 229, due to the blessings that are PPV money and brand endorsements.

Dana White has more than hinted at an interest to make something happen. Is that something a cage fight, we can never tell. But shop was talked. Reportedly, both Hasbulla and Abdu were offered only $1.5M each, which is likely not enough. Hasbi’s manager at the time, Asxab Tamaev, pretty much said that he got Abdu onboard, and shared what seemed to be Instagram DMs (they honestly seem fake) with Dana White. However, White has said in public that he thinks there is a lot of potential there.

Apparently, Dana White loves Hasbulla. Make no mistake: that out of all the people who can host a fight like this, Dana White is the likeliest. This is a video from Khabib’s official channel, where Khabib himself says that Dana wants to “sign him”, but there may be “doubts on his weight class”. For all you can surmise, Hasbulla wants to turn pro. If there’s one thing we know about him, it’s that he doesn’t want little nibbles of the pie.

In December, Hasbulla had a media appearance at an Eagle FC event. He said that while he’s in touch with White, no offer was made to buy their fight. And that Tamaev photoshopped his DMs. By this time, Tamaev and Hasbulla already had a fallout, and the he ceased to be his manager.

He also called Abdu a “singer”, as if that were meant to be an insult. Ice in the veins.

Interestingly, Hasbulla also said in the same interview that he doesn’t want the fight right now. But his public appearances say otherwise. In October, both Hasbulla and Abdu Rozik attended UFC 267. And they met each other. You can guess what happened next. This is 5 months after the very first clip.

And then there was a little Mexcian standoff between the two in February this year. It was mostly photos and smiles, but neither could resist trying to sneakily throw a jab here and there at the other. That same month, Hasbulla appeared on the Wafflin’ Podcast by Joe Weller (the same one who KSI beat), where, among questions of what true love means, he was also asked who the most famous contacts were on his phone were. He mentioned Dana White, only to say that the fight was unsure but a possibility. I think Hasbulla would benefit a lot by being in a nice little committed relationship. It is short king spring after all.

And then the Barstool Sports interview happened, where he talked about having Abdu "on sight".

But none of this is relevant, which is where the alternative answer to the hold-up applies: they don’t need it anymore. They might not have ever needed it. Both of them can continue to tease us with the idea of a fight without ever having to truly follow up. They can show up in the same place, look into each others’ eyes, but not crush each other, and the world will go wild. They have little against each other, and this could very well be just playing characters, sometimes at the risk of being too into the game. All it might be is mutually beneficial in increasing their ever-growing cult — like how Logan Paul admitted for Andrew Tate. I mean, here’s them smiling wide-eyed, in what looks like the same room where they had the first scuffle.

There may a few parties, like the Russian Dwarf Athletic Commission, that believe that a fight like this is unethical and exploitative; that it doesn’t draw attention to actual sports that dwarfs attempt to make a mark in. But of course, this is no legal regulation. Vegas would sell out twice over if this fight happened.

And if they ever decide to do the fight, they’ll earn bags of cash. But does either of them really want a fight right now, when they’re blitzing their cults in this world? At one point, it was debatable whether one of them wanted the fight more than the other. It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that Hasbulla has been associated with, and asked about this feud way more than Abdu. Hasbi has been the man who’s talked to Dana White, and hung out with Khabib and other MMA stars. Abdu is just a bus rider, a “bum”, a “singer” to him.

It’s likely because Hasbulla harbors ambitions to be a pro, or a true MMA insider, and NOT because he desperately needs this fight more than his arch-rival. He’s busy boating with Shaq, creating NFTs, riding the fly-est supercars, punching superstars, and being a real one.

And lets’s face it: he has a much better chance than KSI at turning pro.

I doubt Abdu could care less either. He’s slated to enter one of the biggest film industries in the world, alongside the biggest Eid-day superstar in the world. He’s passionate about his musical career, and meeting his idols. He’s an extroverted charming multi-hyphenate who truly rocks whatever he wears, and he’s comfortable in his own skin. For him, making fun of Hasbulla as a all-talk-no-shower is just a side thing he likes doing when he can. He’s enacting skits with other influencers, eating at (and endorsing) the fanciest restaurants, all the while being grateful to all his well-wishers. And creating NFTs, of course.

No one expected either of them to make it big, but at 3’3”, their heads stand above the clouds, while their feet are firmly on the tallest accessible floor of Burj Khalifa. Did I say spring? I really meant cruel summer. They’re on top of the world, and we’re just NPCs in their video game.

KO.

A note of thanks to the following people who helped make this piece happen: Saumya Saxena, Aditi Singh, Siddharth Rao, Rasleen Grover, Nicaia D'Souza, Siddhansh Agarwal! Getting gem quotes/insights from people in the industry, and becoming an MMA fan overnight (thank you Sid), were only possible because of them.

I will be taking a break from Hot Chips for now: I have a reading backlog that needs clearing, among other commitments. I sincerely believe that reading makes me better at writing, and there are a couple of books and more than a few newsletters I’ve had my eye on. I haven’t read anything new and meaty in a while and it’s high time I get out of this slump. I will be back in November, with the first piece of the second year of Hot Chips.

Meanwhile, don’t feel too shy about sharing this piece, or my newsletter to your friends, family, family friends, partners :)) If you have thoughts about this piece, I’m @pranavmanie on Twitter, where I’m a little too active for my own good. I respond to messages fairly quickly, except creepy stuff or scam invites.

Until next time :)

Hooked! ain't finished yet. BTW been following ya and "clap" for a huge leap in your writing style

Brilliant issue! One of the best that I've read this year. The research is absolutely on point!

Can't wait for the next one in November!