Hook, Crook, Book

A bit on the nature of crime and masculinity in pop culture.

Hi!

First of all: if you haven’t yet, please do consider moving Hot Chips from your “Promotions” tab to the primary inbox. You can add “pranavmanie@substack.com” to the primary inbox filter on the search bar above.

I had thoughts about a piece of media I just consumed, and felt like I couldn’t hold it back in. Yakuza 0 is a stunning game, and I hope everyone gets to experience it. I mention a bunch of other media alongside the game in this, so I’ll clear your first fear regarding that — this is a spoiler-free article!

Regular programming will continue — I have, yet again, put myself in the throes of high creative ambition (which makes this piece a nice breather also). But I really want to write the next piece, and the one after that. Super excited (and nervous) about the effort it will take.

Such pieces also do me good: I remind myself what structure looks like. I love having a newsletter for trying out new ideas and experiments like this.

As for the backing track, I thought about a killer song with a crime story. But then, I realized, this is more about being a man with a code. So I went with a track that made more sense than any other, and as the piece progresses, you’ll see why. You have probably heard it before :)

Happy reading!

“I'm not the guy you kill. I'm the guy you buy! Are you so fucking blind that you don't even see what I am?”

It’s been a long time since I gave a movie an instant 10/10, until I watched Michael Clayton earlier this year.

It has earned a spot in my all-time list, thanks to a tight script, great acting, and an anti-hero you want to root for. George Clooney has a bit of a history playing distressed chip-on-the-shoulder characters. Michael Clayton, Bob Barnes, Ryan Bingham, and in some ways, even Danny Ocean. No wonder I love the dude so much.

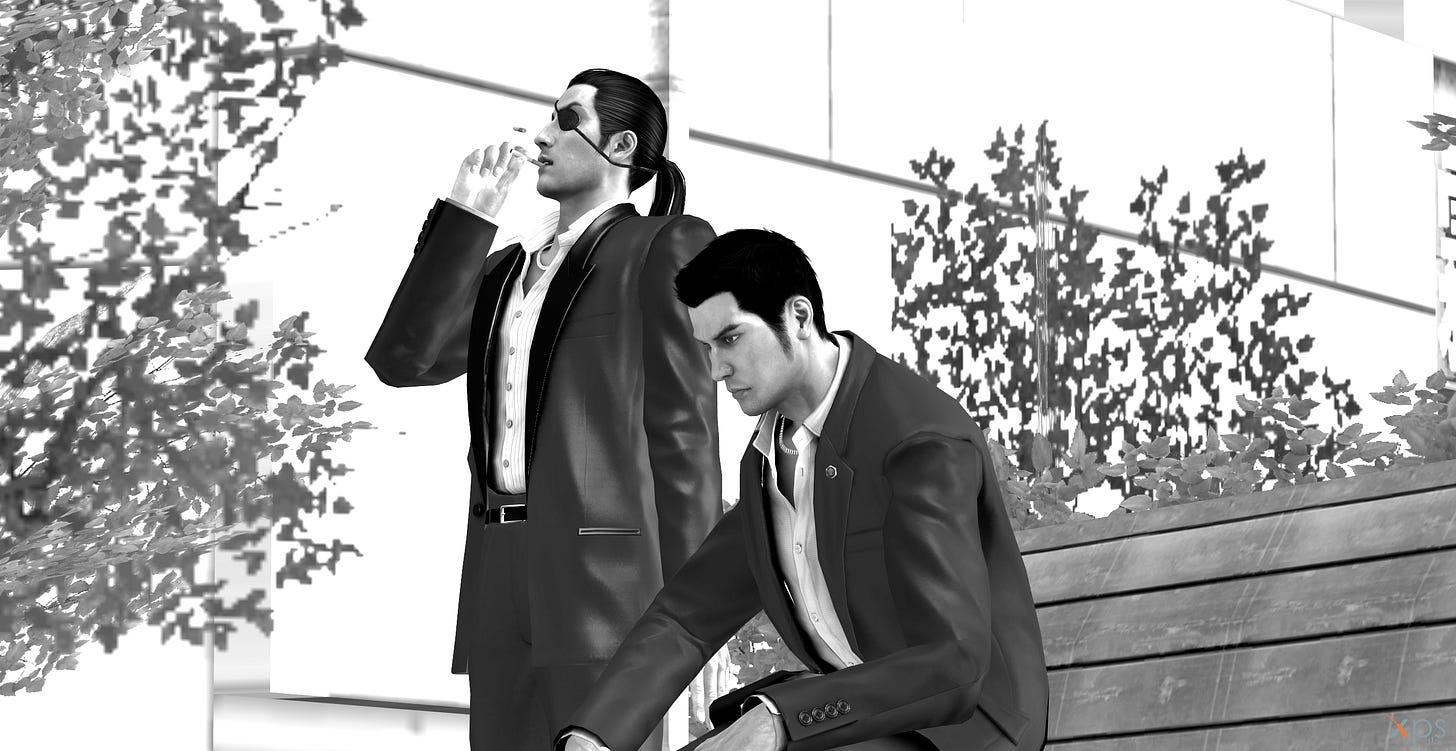

This post isn’t explicitly about Clayton, at least not for the majority of it. But the first quote feels tailor-made for Kazuma Kiryu and Goro Majima — the two playable characters of 2015 hit video game, and my current obsession, Yakuza 0.

I find male characters who believe in brotherhood, and who always feel like they have something to prove, very charming. They might be lonely, and their sense of belonging is consumed by where they work or who they work for. Make no mistake, they see no easy escape from their lives. They rely on only so many people in their lives and will almost always look stiff. Their default mode is to be hands-off — don’t ask questions about where the money comes from. They may or may not care about a hopeful world, though not really what you would call cynical.

In short, they need therapy.

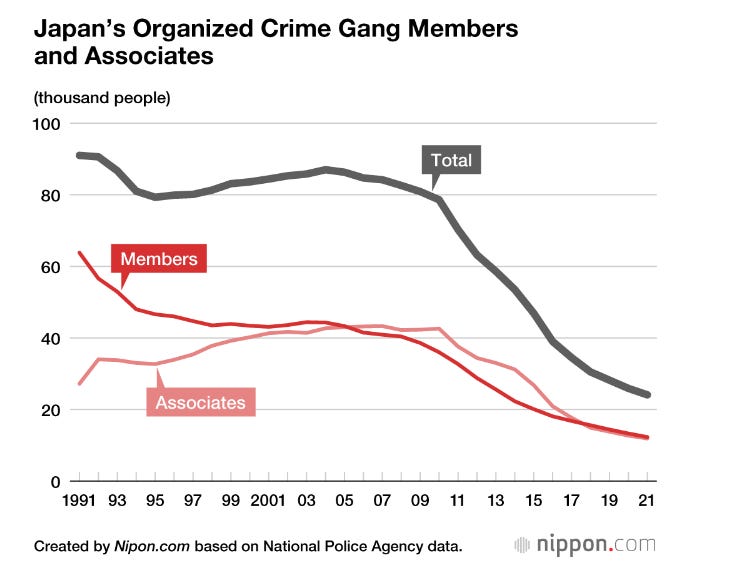

Yet, they believe in having honor and a conscience. For a setup like the extremely respect-based yakuza, somehow, it makes sense. They have weird ideals about giving and taking that will not fly in any world except the one they have constructed. With law enforcement in Japan becoming significantly tougher, the yakuza are a dying breed in the 21st century. Dwindling numbers, lesser sources of income, and being forced to adopt a legitimate way of life.

Money For Nothing

In Yakuza 0, you play as two characters who you might just mistake for Ryan Gosling’s driver character in….Drive, of course. Remember him? Stiff face, extremely lonely, consumed by driving, very hands-off until he feels like something around him has morally decomposed into the ground.

Yakuza 0 is set in between December 1988 and January 1989, shuttling between the fictional red-light districts of Tokyo and Osaka — Kamurocho and Sotenbori, respectively. Both areas are named after real-life districts Kabukicho and Dotonbori. The game has been lauded for making scarily exact replicas of the real-life areas. This Reddit user does a shot-by-shot comparison between Kamurocho and Kabukicho. The latter is known for being one of Asia’s biggest nightlife districts.

While released after Yakuza 1-5, Yakuza 0 is a prequel. And the level of detail of Kamurocho has been stunning — Kotaku published an entire treatise on how Kamurocho’s identity changes over time. Tall buildings present in Yakuza 5 that didn’t even start getting built in Yakuza 0. The franchise spans 3 decades, from the 1980s to 2016, when Yakuza 6 was released. And new constructions play more than just a visual placeholder in the game.

Buying land was all the rage, owing to Japan’s extraordinary asset price bubble until it burst in 1992. The center of the game is a pea-sized piece of ground that is valued at a billion yen — around USD $8M in that time. The plot is key to Kamurocho’s revitalization project — in which, of course, a yakuza clan called the Dojima family has lots of stake.

The yakuza have always been conscious of their public image. Most notably, members of certain gangs were among first responders post the devastating 2011 Tohoku tsunami that caused the Fukushima nuclear disaster. Protection money was a common source of income for the yakuza, but they ensured nothing happened to the shops they were protecting. Common business owners might even have dealings with them.

In a way, much like their Italian-American counterparts, the yakuza have alternated between “necessary evil”, “Robinhood”, and “downright evil” when it comes to civilian perception. However, that perception is defined by whether there’s a direct victim at the end of the crime.

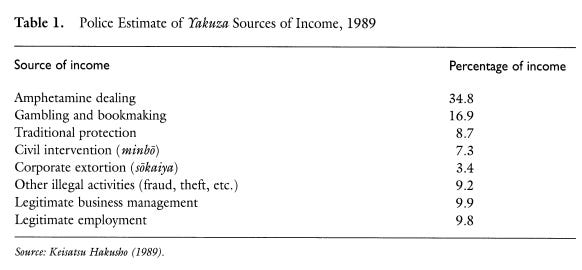

Or so says this Oxford paper by Peter Hill. Hill studies how Japan’s economic boom (and ensuing collapse) influenced how the yakuza operated. Gambling and protection were foundational sources of income. In fact, the yakuza get their name from a losing hand in a Japanese card game called oicho-kabu. Loan sharking, prostitution, extortion were pretty common. Drug trafficking became a massive source of income by the 80s, displacing gambling. But as long as this didn’t result in a murder or a theft — as long as it was victimless, the public was okay with it.

It’s funny that meth is listed as a top source of income: the yakuza live by an unwritten code called the ninkyodo. One of its tenets is that consuming or dealing in drugs is a hard no-no. I suppose money makes the world go round or whatever. Probably what Walter White thought, too.

This piece by the Japan Subculture Research Center seems to have been informed by a yakuza boss himself. He says that yakuza extortionists are driven by a sense of justice: “If you’re being blackmailed by the yakuza, obviously you’ve done something bad and deserve it. We’re enforcing social justice and fining people for their misbehavior. What’s wrong with that?” Another member likened the sokaiya (racketeers) akin to the fourth estate of Japan — because like the press, they would dig up information on big corporates and threaten to expose them, those companies would now be (ideally) forced to behave. I certainly don’t believe this, but it’s also not necessarily a crime with direct victims.

And then the yakuza found, quite literally, a land of opportunity. Police countermeasures had driven them to find new ways to earn cash. In the 1980s, everybody and their mothers wanted some land, bought like Japanese hot cakes.

The yakuza ventured into the construction business — Hill estimates that in 1990, construction alone would have netted them 800M yen (upwards of $6M). In Yakuza 0, there are instances where gangs hire homeless people to loiter around buildings in order to reduce the value of the entire edifice. Silent, unspoken threats are made to owners of flats in such buildings — or money is thrown at them. In a similar vein, gradually, yakuza started placing a ton of money in the stock market.

In such examples of white-collar crime, relationships and information are worth gold. There is a price attached to information — which could make or break someone or something. You know someone, who knows someone, who knows someone. And the yakuza and the state have often had mutually beneficial relationships — the state would hire them to throw out labor unions, or anyone who resembled leftist ideals. The state-yakuza symbiosis allowed the yakuza’s real estate business to thrive.

There’s a brief on the yakuza business by — of all institutions that could make one —economics consulting firm FTI Consulting. The firm quotes one slick example from 2008 (*gasps in economics*) of two yakuza faking a job at a trading company, presenting a sound investment in what seemed to be a company invested in renovating Japanese hospitals. Of course, it was a Ponzi scheme — worth nearly $1B.

If you really want your mind blown, the yakuza’s most important family — the Yamaguchi-gumi — is often touted as Japan’s 2nd largest private equity fund. That’s what information sells for.

Man’s Gotta Have A Code

The game makes you feel the importance of the price of information immediately. Both Kiryu and Majima feel overwhelmed by how much information is being thrown at them. They feel like the world is moving way faster than they had ever imagined. For both, age-old values of brotherhood and humility held priority. But seeing those fade away in the face of a gold rush makes them helpless. The two beat physically strong opponents early on, only to realize that the men who rule them can’t even flex a bicep — yet are invisible hands, puppeteering everything else.

An orphan, Kiryu joined the yakuza because he wanted a life where people around him would respect (not fear) him. A parallel vigilante with a strong moral code that may sometimes be in defiance of the law but is otherwise going to do the right thing. He has a no-kill policy: as a user, you can’t get him to kill anyone in the game.

Majima wants back into the yakuza — a moment of brotherhood cost him membership and an eye. Now, he runs a cabaret, and it’s doing really well. But money doesn’t motivate him, and he doesn’t care about much else. While he wants back in, he discovers that much has changed about the yakuza, in an ugly way. But that’s how Majima also finds out he has a moral code. You can’t get him to kill, either.

Of course the game has violence — a slick, state-of-the-art fighting mechanism inspired by multiple martial arts ensures that. But the most powerful people are those with enough chit-chat material in their veins; they leave the violence to their junior employees. This quote from a game villain says all about how flexible the meaning of being yakuza is:

“I was the yakuza mint, but somewhere along the line, gettin’ bloody started feeling like a pain in the ass. I figured out that bein’ the smart guy takin’ baths in his cash was a helluva lot easier.”

The game takes no time in throwing you into some difficult boss fights, only for you to realize that those still have a template you can follow to beat. Having a finger cut for dishonor — yubitsume — is the last thing they need to be worried about.

Much like Ryan Gosling’s Drive character, neither Kiryu nor Majima is really the type to cry. But they end up doing so as the story progresses. While the nature of crime changed for the yakuza, the level of greed didn’t. In a way, the price of information also included the sanity of those involved in it. Fighting was the easy part, living with one’s own choices was the toughie. Especially when you willingly took the high road that would have risked your own life but was still the right thing to do.

(Moral codes? In this economy?)

This particular theme of Yakuza 0, of fighting something you can’t see or understand, is eerily reminiscent of No Country For Old Men — one of my favorite movies of all time. The old man in question is a sheriff played by Tommy Lee Jones, but you feel like you don’t see enough of him in the movie for the story to be about him. Yet, he makes one of the most fateful lines I’ve ever heard about the nature of good and evil — and why this new evil is a no-fly zone as far as he’s concerned:

“The crime you see now, it's hard to even take its measure. It's not that I'm afraid of it. I always knew you had to be willing to die to even do this job. But, I don't want to push my chips forward and go out and meet something I don't understand. A man would have to put his soul at hazard. He'd have to say, "O.K., I'll be part of this world.”

Kiryu and Majima seem to be under 30, so not even half as old as the sheriff. But assuming that honor doesn’t exist among criminals, both of them entered the wrong profession. Kiryu’s (good-natured) naivety and kindness blindsides him from seeing ahead. He believes in living by a code — much like the sheriff. He also believes that if he faces a nemesis, they must also have a code. He’s devastated to find out that that’s not true anymore.

Besides forbidding drugs, the unwritten ninkyodo covers a few other major points:

Treat your oyabun (the head of a yakuza family) with respect

Don’t steal from/rob the everyday man

Don’t mess with another gang member, or be indecent with a member’s partner

Be chivalrous and helpful to people in need

This code explains Kiryu’s gradual dissonance and disillusionment with the yakuza. Historically, the yakuza came from two of the lowest social classes in the 17th century — the tekiya (who were traders) and the bakuto (gamblers). Being wielders of not just wakizashi swords but also social justice was supposed to be natural for them — especially as a group who started from the bottom. It’s why Kiryu had wanted to be part of such a ragtag.

[Fucking hell, I have never been able to store a wakizashi or a katana in Kiryu’s inventory throughout the game. Sure, maybe it’s because [redacted spoiler], but bro, what the hell?]

What explains Majima’s broken relationship? Being out of the yakuza for 3 years certainly adds to it. He wanted to get back into the game. Seemingly, he was ready to do it at any cost — be it 500M or 5B yen. However, killing a civilian was not really something he was willing to do. It’s also not really something that the ninkyodo approves per se. But like Kiryu, Majima also doesn’t know where his purpose lies if not for being yakuza.

In fact, in the game, Majima derides a yakuza boss for having slipped from his old ways of being known for beatdowns, and turning into a sleazebag who can’t see beyond luxury. Even if he did re-join the yakuza, Majima can’t contemplate whether being a member means the same as it did a few years ago. That such a pivot really made that boss less of a man — less of a modern-day samurai — in Majima’s eyes.

Either way, lose-lose for him.

This unwritten set of rules is also intertwined strongly with what it means to be a man, and how one can prove themselves worthy of that dignity. Almost no deal in the game seems to be written in stone — I have no idea if the yakuza really believed in someone’s word. Yet, the ability to look someone in the eye when he’s been humiliated is accepted as an inherent characteristic of being yakuza. No wonder they have often been compared to the samurai.

I’ve never read any bro code that exists in real life. But, from what little I know and have experienced in life, these rules are not very different from what it means to “be a man” for civilians like me or you, either.

Admit it, being yakuza sounds cool. There’s a reason why The Godfather is so beloved: the likelihood of a dude calling the story one of Mike Corleone becoming boy to man is pretty high, regardless of Mike’s body count. It’s why we find the energy of Goodfellas extremely infectious. Even when we know that there’s no honor among criminals, a man is defined by whether he rats out someone or not. Robert De Niro said it best:

“I'm not mad, I'm proud of you. You took your first pinch like a man and you learn two great things in your life. Look at me.

Never rat on your friends. And always keep your mouth shut.”

God of Death

Michael Clayton is a fixer at a top corporate law firm in New York. I doubt that fixers exist in Indian corporate law, but Clooney has said that there are some real-life events that inspire the plot of the movie. Fixers do exist — Donald Trump had an infamous one named Michael Cohen. And his type has received some lavish Hollywood treatment: Michael Clayton, Inside Man, even Pulp Fiction with the Harvey Keitel character “The Wolf”.

I won’t tell you how the movie ends. But while Clayton shares a lot of similarities with Kiryu, Majima, and Ryan Gosling’s unnamed Drive character, there’s one key difference that helps him stand out: he understands the ever-changing nature of crime because he’s also one of the people perpetuating it.

(“Say what you will about lobbying/fixing, at least it’s a legitimate business.”)

Clayton benefited from being fronted by a legal entity like his employer. His job is to “clean”, like a janitor — as he’s so often called in the movie. Clean the mess that his employer’s clients have left behind — ideally so that it never sees the light of the court’s day. Sometimes, such messes may involve accidental manslaughter.

Unlike Kiryu and Majima, Clayton knows the price of information. Sometimes, he sets it too. He never resorts to violence — he doesn’t have to. He knows that by the end of the day, the last person he spoke to will get his — or his employer’s — work done.

But Clayton isn’t happy. He may be great at fixing, but he doesn’t want to do it. He’s going through his own phase of disillusionment. His face betrays him for all 1.5 hours of the movie — he doesn’t believe that such work adds any value. In any other sane world, fixing should have been illegal, and he would seem to be the first to admit that fact. It certainly isn’t morally fulfilling.

But he’s invaluable to his employer, and he has a family member’s loan to pay off. He’s trapped in his own expertise. It’s a job that — as evidenced right at the beginning of the movie — led to a divorce, and created some distance with a son — that he’s trying to bridge. In short, Clayton needs therapy and to quit his job.

Then, like Kiryu and Majima, Clayton is faced with crime turning its evilest head. Something that even he couldn’t see coming. And it shatters every excuse he had for his sorry profession. The kind of white-collar crime that the yakuza also ventured into starting from the 1980s, but fronted by legitimate capitalist institutions. The kind of crime that will most likely require a symbiotic relationship with the state.

A friend once told me that Yakuza 0 is the most Marxist game he’s ever played. I’m not entirely sure, because my real estate portfolio and cabaret club business in-game seem to disagree. But story-wise, he might be on to something. The way I feel about Yakuza 0 and Michael Clayton is very similar, especially in their critiques of capitalism and how it forces men to think about their manhood.

You know what they say about protagonists, right? They are neither heroes nor villains, but tragic main characters whose own decisions may seem to set them up for their own downfall. In real life, me or you would never dream of interacting with a Kiryu, a Majima or a Clayton. We would either dismiss them as mercenaries with no real allegiance, or criminals who only understand the language of violence and blackmail. Or just a lowlife in general.

But in video games, movies, and books, you want to root for them. Sure, they’re anti-heroes by virtue of being in professions more morally ambiguous than most (something about there anyway being no real ethical consumption under capitalism). But you want them to win. You want their choices to make sense. Because even in a world with no real ethical consumption, you’ll meet aplenty crossroads to do the right thing.

And for the kind of character that I describe in this essay — that is defined by where they come from, who they are, and who they know would have been if not for this world — reducing them to just one dimension of being undesirable simply by virtue of being criminals/fixers feels like a mistake. Kiryu wants to create his own definition of being a yakuza: one for whom sticking by his brothers matters more than climbing up the ranks by hook, crook, or book. Majima is too jaded by the life for him to be conventional — yet mentions of his loved ones arouse his soul.

You want these antiheroes to reunite with their children, or their siblings, or successfully protect the ones they love. They probably might not succeed, because that’s how tragic heroes are often written. But for that one moment where I beat the fuck out of a dipshit yakuza boss who crossed me (as Kiryu/Majima), I cleansed a part of my soul. Or for that moment where Clayton does [redacted], or Ryan Gosling’s driver character does [redacted], I am okay with there being a “victim” on the other side. Or when the fucked-up Logan — not Wolverine, Logan — takes his adamantium claws out. Or when The Punisher goes all guns blazing.

I love the male antihero. I will always hope they get a happy ending. It’s a tall ask, because choices can leave behind trauma. Yakuza 0 ends in a way where the after-effects of those hard choices shape the lives of the individuals involved forever. You ask yourself if such choices matter in a world that is so grey. There’s a moment when Kiryu defends his choice of suit color to his oath brother Nishikiyama:

“I’m not feeling black or white these days”.

I don’t know what happens in Yakuza 1-6. I don’t know what becomes of Kiryu and Majima after this, and how they cross paths again. They will. Maybe, for all I know, they could fight each other.

But having seen Drive, Michael Clayton, Logan, Deadpool, The Punisher, Jesse Pinkman, or the million other male antiheroes that direly need therapy, I know why both of them needed to win.

Until next time :)