Sound Logic

The business of running a music festival in India, and building a culture of gigs.

Hi everyone!

Between work, falling sick (a bit too much), and other personal delays, this piece is late enough. I’m surprised that the problem was not procrastination this time.

So back to work! I’ve teased this piece long enough on my socials. Now I’m super excited to show you what I was working on, and who I have been interviewing for it. Appropriate playlist attached; I’ll leave you to the rest. Happy reading :)

In December 2022, Spotify rolled out a unique rewards program in India — the first (and so far only) country to get access to it.

If you use their Premium Mini (₹7/day OR ₹25/week) consecutively for 10 days, you would be entitled to another week of the subscription for the shortchange amount of ₹2. One heck of a program by this product manager named Szymon Kopec.

However, what I really want to draw attention to is the timing of this plan. The original Premium Mini plan minus the new rewards program was introduced in India in December 2020. Before the Premium Mini branding, one day’s usage of Spotify would cost ₹13. And one week’s, ₹25.

Spotify has shown signs of remarkable growth in the last 3 years. Since its launch early 2019, it went from 2M active users, to around 6x that number in the third quarter of 2020. Leadership from the company, from the VP of markets to founder Daniel Ek himself have repeatedly noted that India is an important market for them, and India is one of their highest engagement regions. But engagement unfortunately doesn’t always mean money, especially you keep finding yourself reducing your plan pricing to cater to a country known for not paying. Ask any consumer entertainment company — ask Netflix, and they’ll all tell you the same thing.

It’s hard to crack India as a market for entertainment.

Here’s a killer dashboard from Anton Averkiev comparing the price of one month of Spotify Premium across countries, adjusted against the American dollar. The “0%” bar is at $10, which is the cost in the US. India is nearly 600% cheaper.

This is part of a much larger interesting pattern of consumer behavior towards how we value art and artistry, in any form. Foreign players don’t seem to be very sure of whether there is willingness on the behalf of Indian consumers to subscribe long-term to their content. And this is not necessarily a trend that’s only seen among Indians that can’t pay — it’s sort of a running joke to have more than enough money to pay for YouTube or Spotify Premium but never give in to the constant flux of advertising that these platforms throw free users into.

We saw this behavior in all its glory in the first 3 weeks of January, when everyone (and their mother) who had bought a Lollapalooza India ticket was suddenly looking to resell it in black to anyone who would go instead.

Encore, Do You Want More?

From the time that the advertisement for The Police’s 1980 fundraiser concert included showing an Indian policeman, to having elite domestic IP like Weekender, Supersonic, to international IP like Global Citizen and now Lollapalooza, live music has come a long and fruitful way.

Michael Jackson has only ever toured once in India, and that was as a fundraiser. For some very-odd reason, the Shiv Sena declared this concert that cost a then-whopping INR 5000 / seat tax-free. Quite objectively, tickets for big concerts today are cheaper than what they were then, and concerts back then were hubs of the social elite who could drop major dimes in a fancy hundi.

However, it’s not like artists never paid us the respect we’re due as die-hard eaters of good entertainment. In 1993, Bryan Adams played in Bombay, beginning the start of a beautiful relationship that had him come 4 more times to the country (most recently in 2018), and solidified his status as India’s 2nd-favorite Canadian behind Akshay Kumar (sorry, Justin Bieber / Trudeau). Enrique Iglesias came in 2004, with tickets priced at 600 and 900. And oh baby did he like it, enough to come back in 2012.

A landmark moment for India’s live concerts space was Iron Maiden gracing Bangalore in 2007 — marking a peak for the city’s metalhead scene. It’s actually bewildering that we’ve been graced by Iron Maiden (2007, 2009), Metallica (2011), and Megadeth (2012) in the pre-streaming era, where it would have been difficult to prove their Indian presence via direct album sales. Megadeth were the headliner for what was just the third edition of Bacardi NH7 Weekender, organized by OML.

While Weekender started in 2010 as an answer to UK’s Glastonbury, an entrepreneur named Shailendra Singh decided to host a buffet of electronic music in Vagator, Goa, and called it Sunburn. In time, it grew to be the 3rd largest dance festival in the world. Axwell, Martin Garrix, DJ Snake, KSHMR, the world’s best EDM acts would show up year after year in Goa just for this. And for a good while, this spawned an obsession that India would have with electronic music. In 2013, also in Goa (Candolim), VH1 launched the multi-genre festival Supersonic.

Northeast India also launched a few festivals of its own, with rock and folk-focused lineups. The Ziro Festival was started in 2012 by Bobby Hano and the guitarist of Indian band menwhopause Anup Kutty. Every year, the Apatani tribe of the Ziro Valley provides its resources to a festival renowned for not just the music, but its picturesque backdrop. In a similar outdoorsy vein, the Orange Festival (in Dambuk, Arunachal Pradesh) is a unique blend of live music and adventure sports, while sporting a diverse lineup focused on highlighting regional talent. NH7 Weekender is held in Shillong.

Towards the later 2010s, India began to see international franchises put their stake in the country’s music listeners. In 2016, the Electric Daisy Carnival, whose flagship event happens in Las Vegas every year decided to branch out to India for the first time. So did New York’s Global Citizen Festival — a fundraiser concert for late teens and early 20-somethings, organized by the Global Poverty Project, and curated by Coldplay’s Chris Martin.

Both happened in November 2016. Someone high up just said “Honey I Shrunk The Kids” “Kids I Shrunk The Money”, which damaged our economy, and also killed EDC India to the point where they never came back again. Coincidentally, Global Citizen came to our homeland because PM Narendra Modi infamously wished for the force to be with those attending the New York edition in 2014.

Large corporates have also notably used fests / carnivals as lead generators for their business. In 2019, the inaugural OnePlus Music Festival was held in Mumbai, headlined by Dua Lipa and Katy Perry. So was the first edition of Zomaland — part food fest, part music festival. In 2022, for a Feeding India fundraiser, Zomato had Mumbai rollicking to the AutoTuned magic of White Iverson himself, Post Malone.

Between fundraisers, corporate festivals, consumer IP (including one-off concerts), India’s market for live entertainment has set impressive benchmarks every year and is growing more diverse.

Estimating the market for live music in India is quite a tough nut to crack — when I have a guesstimate I’m confident with, I will certainly let you know. Why it is so is because how fragmented the market really is — across genres, across lineups, across different franchises and stakeholders that choose to enter this space.

Songs of Experience

Yet, for all its splinters — how is it that almost every major large-scale live event in India has to happen in Mumbai — specifically Mahalaxmi Racecourse Road?

I pose this question to Roochay Shukla, Senior Marketing Manager at Outdustry — a market-leading artist services and rights management firm whose clientele includes Dua Lipa, Diplo, Major Lazer, Lauv, Jungle and India’s own Sez On The Beat. He oversees marketing and promotions across all media for his clients.

He takes me through the capacity of each kind of festival. An ancient rundown Bollywood studio — the kind that burnt down in Om Shanti Om — hosts the Mahindra Blues Festival, which saw 3000+ attendees. But go any bigger than that and it becomes harder to find a good venue. 5000+ people will need something like Jio Garden. If you’re playing to over 10000 people, you might as well do it at a cricket stadium. Indeed, when U2 came to India for the first time in 2019, they performed at Mumbai’s DY Patil Stadium.

Mumbai and Pune are the usual suspects when it comes to deciding on a venue for a music festival. For the last couple of Weekenders hosted in Pune, the venue has been Mahalakshmi Lawns. Lollapalooza was hosted on aforementioned racecourse in Mumbai, which has a slick set of apartments that overlook the track whose rental I’m too afraid to enquire. Not least because the artists who have played there include — Ed Sheeran, Martin Garrix, The Chainsmokers, deadmau5, and now The Strokes.

3 of the 5 names above are essentially EDM artists. The evolution of our obsession with electronic music has an extensive history. Initial lineups of IP like Supersonic have always been electronic-heavy. Here’s a side-by-side comparison of Supersonic’s 2015 and 2023 lineups, respectively. Notice the difference in the top 4 billings in each image? The top 4 in 2015 were all DJs.

The early 2010s saw different subgenres of house music — progressive, electro, deep —dominate the charts. The most important names advancing that music find their place in the lineup on the left. By 2014, India had….ahem, housed nearly every big name in electronic music. Swedish House Mafia, Armin van Buuren, UK legend Fatboy Slim, and every other name mentioned over the course of this piece.

“The EDM bubble in India exploded when electronic bridged pop”, says Roochay. Pop’s more ear-friendly, bouncier elements balance out the harshness of the percussion used in electronic. While not strictly electropop like Dua Lipa or Calvin Harris, this music was still catchy and accessible. With respect to India, we saw this trend peak when Nucleya decided to pick up a console and put the shehnai and every Indian percussion instrument he knew into his track.

And made thousands of people scream “ek bhayanak atma hai” in perfect unison.

Nucleya, Marshmello and Alan Walker were the biggest beneficiaries of this love for poppy house music. While an Axwell or a Hardwell still brought on an extremely loyal fanbase that loved to rage, these 3 (and their like) were absolute crowd pleasers. By this time, due to YouTube and the advent of streaming in some capacity in India, artists had begun realizing that India was no longer a market they could ignore. After the first time they would perform in the country, their social media could potentially increase manifold by the sheer droves of Indian fans.

I speak to Devarsh Thaker, ex-VP of Content at OML, and someone who has regaled me with stories of chilling with Chet Faker. He’s overseen marketing for 5 iterations of Weekender. To him, an artist showing out their love for India in tweets or stories is not surprising. “It’s beautifully engineered by artist management”, he says.

What does he mean? Skrillex, who has been to India just once in 2015, has, for all intents and purposes, a song called Mumbai Power. His erstwhile management — Warner Music — might say something like “hey, Sonny, you have at least 3 million fans in India. Do a little something for them?” Or Marshmello, who is represented by Universal. Akon doing “Chhamak Challo” was not a moment of sudden love for Indian tradition from his end. It was a calculated move, whose seeds were probably sown a few months before the release of Ra.One when Akon has performed live here.

There’s a reason why, without fail, international artists across genres put out “Happy Diwali” and “Happy Independence Day” wishes on social media.

Over time, the hype around progressive house plateaued — not necessarily reduced, because they still sell out shows in India like hot cakes. But the interest in that subgenre has splintered into other forms of electronic music, too — most notably, techno and trance. Live electronic shows promise a night of extreme, nonstop partying and headbanging. A culture so distinct from any other genre, and certainly not for the faint-hearted.

In India, if the live gigs of the 2010s were dominated by electronic music, the decades before that clamored for rock. We’ve witnessed major rock festivals like Rock ‘n India, Independence Rock, and Great Indian Rock Festival — the former brought in Iron Maiden, Metallica, and Slayer. “College fests would always have ONE Indian rock band perform at the end”, recalls Roochay. In fact, Independence Rock was born because the principal of St Xavier’s Mumbai had barred Indus Creed and Mirage from coming to their annual fest Malhaar.

However, rock isn’t as hip today. Independence Rock (now revived) and Great Indian Rock Festival died natural deaths of sorts. This is no coincidence — “rock is dying” is an adage that seems to hold up every single year in the streaming age. “The rock fans are always the first to be disappointed when a lineup is announced”, says Roochay. With Lollapalooza India, two bands heavily rumored to be in the lineup were Pearl Jam and Red Hot Chili Peppers — the latter were fresh off 2 new albums in 2022.

The one exception to the supposed perception of rock seems to be in northeast India. Ziro continues to uphold its tradition of being focused on rock and folk, while also giving the stage to more homegrown, regional talent.

In Roochay’s opinion, rock can explain why rap blew up in India — the two genres share similar elements: the fandom, the aggression, the moshpits. The transition of rock to hip-hop could be compared evenly with that of EDM to pop, or that of trance to techno — one of the fastest growing genres in India.

And it’s this diversity that fests have to take into account while thinking on programming lists. With the advent of streaming, and (more importantly) playlists, deciding lineups for fests has become easier, more data-driven, more strategic.

Everyday I’m Shufflin’

Devarsh has had the privilege of having deep conversations with Chet Faker, who told him one day “I’m upset that no one knows my real name, Chet Faker was just an experiment”. It didn’t help that his name was a derivative of one of the popular jazz musicians of all time. Devarsh, on the other hand, wanted him to come — like his song — down to earth. This was his ego talking, the people love him for the music he made under that name. It means something.

However, in 2019, opening Weekender was not Chet Faker. It was Nick Murphy. Chet Faker had taken a sabbatical from 2016 (one he eventually broke). Chet Faker would have had a ton of equipment and a band with him onstage. Nick Murphy just got himself and a sound engineer.

The decision to get Chet Faker / Nick Murphy to headline Weekender 2019 stemmed from the fact that he was touring in Japan and Hong Kong. Of course, this information was also something that the Weekender core team kept a track of through their programming list. Either way, his agents likely put out a feeler towards booking managers of fests, promoters, and labels in India. It would make no economic sense for an artist to come all the way from Australia.

Japan, Hong Kong, Thailand, Philippines, are all top target countries for artists to set tour dates. “The top new tracks on a global Spotify playlist see their initial growth being primarily driven from Thailand and Philippines”, says Roochay. Then Europe takes notice of the song’s growing popularity, and the song blows up even further.

But different entities circle around the Indian market for an artist touring Asia in different ways. One way is tracking growth in different countries — a perennial process that feeds programming lists of fests. But Devarsh tells me of the time when Weekender called Poets of the Fall in 2018. A marketer in OML was tasked with sizing the market (consultant-style) for the legendary Finnish band using its social media following —> what % of it was Indian —> what was the regional distribution of this Indian following. OML narrowed down areas in North-East India are having the most sizeable POTF fanbases. This process would also help with getting a user persona for running targeted ads.

Post the market sizing, and speaking with the respective artist managers, a deal is signed. Usually, the organizer promises the artist with a performance fee, a guarantee on handling any cargo and crew that accompanies the artist, and travel & accommodation requirements. For rock bands, this same performance fee would be very sizeable. But more importantly, the economics of calling a rock band would doubly worsen because the napkin math behind it would say that they won’t generate enough revenue. I would not bet too much on rock bands generating substantial revenue among GenZ in 2023.

Rafael Pereira is the founder of artist liaising agency Cadre, and of his own legal setup Tinnuts. What Cadre does is that after the promoter has signed a deal with an artist to come to India, it takes care of all of their personal and hospitality needs. Cadre has liaised with artists for Weekender, Lollapalooza India, and the Isha Ambani wedding — it must be quite the job to look after Beyonce’s accommodations and wants. Anyway, Rafael confirms the logic of such napkin math in more qualitative terms:

“On New Years’ Eve, electronic artists often play 6-7 shows in a span of a day. They find themselves doing the New Year countdown multiple times in the span of 24 hours — playing nonstop from the start of the new year in Japan, to the same in California.”

Electronic artists are not only more cost-effective than rock bands, but their live setups are highly repeatable. Here’s a simple representation of how genres rank across factors that enable them to conduct shows smoothly:

U2 was brought to India courtesy BookMyShow. Cadre handled the post-booking liaising with U2 for their Joshua Tree tour in 2019 in Mumbai. “One of the toughest productions ever in the history of Indian live music”, recalls Rafael. Promoters were afraid of taking a risk like this after Justin Bieber cancelled all his Purpose tour dates in 2017, right after performing in Mumbai. Again, the U2 Mumbai concert was a consequence of the band touring in Asia.

When the expectation from the artist is much less, or when the artist is significantly more mobile, a Landed Deal is commonly signed. Such a deal contains none of the guarantees behind equipment and crew, but just a fixed fee and accommodation. The artist just has to land themselves in the fest on D-Day and perform. Most Indian artists and international DJs are brought in using Landed Deals because it’s easier for them to manage travel that way.

Naturally, artist costs would take a major chunk of the budget. Devarsh quotes that for Weekender, it would be upwards of 30% of their total spend. I have a few assumptions about what the figure is, and that involves assuming the average price of a Weekender ticket — owing to its multiple tiers (the complete non-VIP season ticket is Rs 4000). Some math tells me that artist fees could easily be more 6CR for a fest of Weekender Pune’s size. It doesn’t involve stage production costs. Assume that for this scenario, the revenue matched the cost of the fest:

Playlists have been an inflection point in tracking artist popularity, and thereby the viability of them performing live in India. “Save YouTube, the consumption of international music is higher on Spotify than any other DSP”, says Roochay. His expertise lies in understanding this popularity in India. 15-20% of the songs in Spotify’s Top 100 tends to be non-Indian music. As of 29th March 2023, 2 songs from The Weeknd’s Starboy (a 2017 album), Ed Sheeran’s Perfect (2017), and One Direction’s Night Changes (2014) feature in Spotify India’s Top 50. Indians can be very loyal music fans, even when the song is 9 years old.

One of the more robust indicators of artist popularity is how many third-party Spotify playlists you’ve been added to. This has become much stronger in the wake of popular playlist curators charging indie musicians for placement. Of course, playlist culture has been running for years now — with a Spotify playlist playing an integral role in making hip-hop the most popular genre in America. Translating playlists directly into live gigs is also not foreign. Spotify India has a desi rap playlist called Rap 91 (our version of RapCaviar), and a playlist to promote indie musicians called Radar India. Both playlists have had exclusive RSVP-only events where the acts in the playlist were called to perform for a day in a small yet sparkly location in Mumbai. For all you know, Spotify could very well launch their own music festival in the future.

Having The Strokes, Imagine Dragons, DIVINE, Cigarettes After Sex certainly sounds like the playlist of a well-off 21 y/o student studying in Delhi University’s lush campuses. With a side order of weed to go with the vibe of the college party.

Dance Now

It certainly matters what the purpose of your music fest is, because that determines whether you’ll be selling tickets to a 35 y/o Pantera fan who laments the rise of pop, or the aforementioned 21 y/o.

I speak to Owen Roncon, chief of business of live events at BookMyShow. Owen oversaw all of Lollapalooza India this year. And he paid a lot of heed to the chatter he heard online about the fest. He understands that the lineup looks like a modern-day Spotify playlist, but this was not entirely deliberate.

“We’ve had conversations with 200-250 bands / artists to get this lineup. We paid heed to the chatter online, and we would love to get more heritage next year.”

Owen said that there are typically 3 layers of audiences at gigs: those who come for the music, those who hang with the music lovers, and those who come because it’s cool. Lollapalooza’s goal would be to convert the third group to the second or the first increasingly every year. There is no particular way to track this, but it would be a good symbol of retaining more customers annually. “Lollapalooza has always been a festival about the discovery of sounds, as opposed to being cool.”

Devarsh looks at it slightly differently, even though Weekender is more about the discovery of sounds rather than being a status symbol. “The minute people start pegging the fest to one artist (likely the headliner), they put a value to the ticket. This is counterproductive to the festival as a whole.” The fest is bigger than any one artist. The headliner will perform only for a couple of hours.

The solution, then, is to market Weekender as a community experience. People love going to Weekender Pune / Shillong in groups of friends. It becomes a fun vacation for them, and Weekender becomes a top checklist on things to do in that vacation. More than this, though, Devarsh focuses on the value of cracking a community around the fest, because these will be lifelong fans. The fest has a tier of tickets called “Weekender Warriors”, that gives you some perks (like a VIP ticket) and a mug that says “I was there NH7 (insert year)”. Some people have as many as 8 mugs.

Paid marketing is also designed to reflect this audience split. While the top of the funnel will be the fans who are there for the experience, the next phase will be to target the “music purists” who are likely coming to see just the headliner — like FKJ, Steven Wilson, or J.I.D. They’re also people who might just buy a single-day pass to see these artists only.

“Who’s your end user?” For different fests, the answer varies differently. Zomaland has a few metrics that they would be tracking besides the success of their fest — ideally, something like the number of Zomato downloads. “This is why Zomaland’s ticketing has shifted to being inside Zomato instead of being liaised to a third party”, says Roochay.

The reason why, for CSR, Mahindra chooses to do the Blues Festival and the Kabira Festival, is their inherent want to establish themselves as a conglomerate (slash-family) that is in tune with the roots of the country. Blues is hailed as one of the fundamental genres of music as a whole — one of its roots, so to speak. Of course, the goal may also be to cross-sell and up-sell Mahindra products at these festivals. You could apply the same logic to why the Sulafest happens in a vineyard in Nashik.

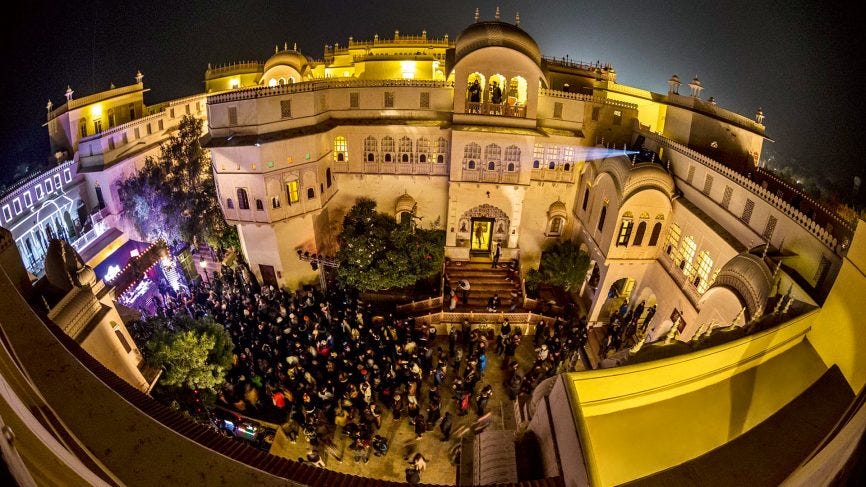

But such end-user differentiation is not just a feature of festivals organized by corporates like Zomato, Sula, OnePlus, or Mahindra. Within purely consumer festivals where the product is the music / experience (as opposed to the corporate brand), there are niches. Magnetic Fields is annually held in December in a lush, rundown palace in the sand dunes of Alsisar, Rajasthan. A phantasmagoria of light and sound, Magnetic Fields’ starting ticket tier costs Rs 12500 — expensive by any standards, but the offering itself is unlike any other in India, where you get to set your own tent and treat yourself to performances in the desert sunset.

You can’t pull off a festival like this without adequately strapped sponsors. Some festivals become synonymous with their longtime title sponsor, like Bacardi Weekender. Every title and associate sponsor will have a stage named after them. Magnetic Fields usually licenses its stages to — Budweiser (or BudX, in this case), Jameson, Corona and RayBan. It should not be a surprise to anyone that alcohol brands are likely the most popular type of sponsor for music fests. What popcorn is to the theater experience, alcohol is to live music.

Once you have your sponsors ready and your stages sold to them, there’s really just one thing left to decide: what will you charge your end user?

In India, this is always a tough question. We are very price elastic. More so for spending on a non-necessity like consumer entertainment. Almost no other country in the world has as many “Early Bird” ticket phases as India has. And even though half of the audience buys tickets closer to the date of the festival, the limited “Early Bird” phase is the biggest litmus test of the potential success of the event.

“Most other nations really only have 2 slabs, while India will have an endless number”, says Roochay. Which makes deciding those number of slabs beforehand really important. Owen tells me that BookMyShow has an in-house formula that they follow and have developed over years of ticketing live events, that takes into factors like disposable income, time of year, their own spend. They create an end-to-end P&L for Lollapalooza India as a whole, based on the average price of one ticket, and how many people they would need to sell it to in order to hopefully break even.

“We ask ourselves ‘would I buy this ticket’ constantly as a team”, says Owen. When you adjust the average price of one Lollapalooza India ticket against the dollar, it nets to around $100. The first general admission tier of the original Chicago event costs $375 — nearly 4x that of India.

And it’s much easier to market a one-off concert where only one artist is the draw. The promoters’ sole job is to make known to everyone that this artist is performing. But for a fest — a bundle, in essence — it’s different. Which is why you can justify Rs 5000 being the price of a Backstreet Boys ticket to Backstreet Boys. Of course, Lollapalooza India’s lineup and scale is smaller than that of Chicago, but it must still be tough to settle on Rs 8000 as the average price for a bundle that features The Strokes, Imagine Dragons, Jackson Wang, and Cigarettes After Sex. Or, if you take Weekender, then Rs 4000 for The Lumineers, J.I.D, and Dirty Loops.

Yet, for how value for money such a ticket often looks, it is still hard to justify to an Indian consumer why it’s fair.

Gandhi Money

Live entertainment in India follows rules that consumer products / services in India often have to. One litmus price test, multiple tiers of pricing, bundling. There’s a reason why a large fraction of OTT subscriptions in India are sold primarily through data plan bundles of service providers like Jio and Airtel — in 2021, telco-bundles drew ~85% of all OTT viewership in India. There’s a reason why Spotify is trying a plan like Premium Mini, and why Lollapalooza India ticket-holders went into panic mode trying to resell their ticket near D-Day.

Lollapalooza India 2023 was enough of a success to return next year. Turnout was around 60000 people in all of its 2 days, which means it sold anywhere between 25K-30K tickets at the least — majority of which were likely sold during Early Bird and Phase 1. The lineup features multiple domestic and international headline-level acts — an impressive feat in India’s history of live entertainment by any measure, all at the early bird price of Rs 5000. What, then, explains the consumer reaction to it?

“The problem doesn’t end there — AP Dhillon, RHCP, Diplo, humein sab chahiye — we want everything”, is Roochay’s take. And he’s not wrong. It’s hard enough to get an international artist that’s touring in Asia to India, let alone all the way from their home country. But this is not messaging that the consumer will be mildly interested in understanding at all. The average consumer doesn’t want to know the behind-the-scenes of how hard all of this is. And as a promoter, you can’t convince the consumer that something is “great value for money” by simply stating the same.

It becomes trickier when the price itself acts as an unpredictable signal, let alone for an experience like a music fest that’s already hard to value. “The minute you bring down the cost, consumers feel the quality is off. But when you increase it, they question the value of it”, says Devarsh. What is then the solution? Devarsh also answers that, and it’s really as simple as building a culture of gigs over time:

“The more gigs happen, the more people understand the value of experiences. It takes time. Quality gigs were once unheard of in India. At a point in time, India had no regulations for accommodating something like Weekender — we had to sit with the police and municipal corporations to build out rules for something that was new to them.”

There are strong signs that this is happening. Both Roochay and Devarsh mention how quickly Bonobo sold out his show earlier this March at a non-music venue like The Lalit. Even for something non-music, Daniel Sloss sold out all of his India tour stops this year — Mumbai and Bangalore went away in 10 minutes. Bonobo was promoted by SkillBox, and we got to see Daniel Sloss (as well as Post Malone) because of BookMyShow’s efforts. Promoters like them are leading the charge on getting artists with all-time appeal across regions.

Large sects of Indian audiences are taking in music trends. Be it India’s obsession with K-Pop (that spurred someone like Jackson Wang coming here), India’s obsession with Taylor Swift (she's….really, really popular in this country), our continued love for yesteryear artists like Linkin Park and Eminem, we have acquired so many contemporary tastes today that any artist worth their salt will be hard-pressed to find an answer to why NOT to come to India.

We’ve also been playing catch-up in a lot of ways. The proliferation of data usage in India (owing to Jio) has led to us consuming a whopping 19.5GB / month, which is apparently 6600 songs’ worth. India is a mobile-first market, that is now being exposed to trends that have been existent for much longer in more developed nations. This is one reason why the misconception of artists only playing in India past their prime exists. The power of our consumption was only unlocked a few years ago. Even then, we’ve been welcomed by lots of international artists during or before their peak. Imagine how much better this could get in the coming years.

On the part of the promoters, the goal is always to improve the next iteration of the festival. With respect to Lollapalooza India, Owen says, “You have no references or guesstimates here. But we had to do lots of tech prep, met with infrastructure hiccups.” He says that BookMyShow is already working on smoothening the kinks out — like redesigning the layout of the fest in order to better the consumer journey, already working on the lineup, and using all the learnings they have received this year.

With time, people will find it hard to move away from how much meatier live entertainment offerings in India will be. 2022 was the first year we saw gigs bounce back from 2 years of being dead. It has been quite the return.

At the end of the day, you can’t please everyone with the lineup. But every year, the hope is to please some more.

Cover photo credit: Martin Garrix’s own Twitter.

Special thanks time!

Chinmay Bhogle, Aaron Barboza, Abhay Sharma — for being incredible help with this piece, wouldn’t have been possible without you guys. You know why.

Supraja Srinivasan, Head of PR and Comms at BookMyShow — for entertaining all of my questions, coordinating the interview with Owen, and chipping in with your own wonderful insights during the chat.

Roochay Shukla, Senior Marketing Manager @ Outdustry — I hope to do a behind-the-scenes for Sound Logic, and much of it will be peppered by my chat with him. One of the most delightful conversations I’ve ever had for Hot Chips. He’s @roochay on IG.

Devarsh Thaker, Marketing @ Fampay and ex-VP of Content @ OML — for regaling me with incredible Weekender stories, insane insights about the music industry, and your own love for Chet Faker / Nick Murphy and Steven Wilson.

Rafael Pereira, co-founder of Tinnuts and Cadre — thank you so much for taking out time for what was a fascinating conversation. I’ve not delved too deep into the legalities of contracts that govern live gigs in this piece, but that’s a conversation in and of itself that I had with him.

Owen Roncon, Chief Business Officer of Live Events @ BookMyShow — for entertaining all the questions I had about Lollapalooza India, and understanding what I have been trying to achieve this piece.]

Kushan Patel and Sunaina Bose, for the usual solid proofreading and editing <3

I will be taking a long-due, long-intended break. Unfortunately, the break cannot be from work because something has to pay the bills :) so sadly no proper Hot Chips in May. However, I might do a behind-the-scenes for an old piece! I’ve been toying with BTS pieces, and while those won’t be story mode, I have enough leftovers to create something fun out of them!

But I will be back in June. With a story I already know I’m going to write. Non-music / non-entertainment, but still very much cultural — depending on how you decide to define culture. It’ll be personal, too. But then again, every piece is :)

I hope you had fun reading this one. As a fan of live music (mostly hip-hop of course), and a so-called patron of the arts, I wanted to write this for quite some time. Please feel free to share it if you loved it! I will also be doing a BTS of this piece in the future where I put all the facts and figures that don’t find a place here. A LOT was left out on the cutting table.

Until next time :)

Your work has inspired me. Will be looking forward to reading more of your work !

TIL, moshpits in hip hop. Interesting matrix on cost effectiveness.